- En

- Fr

- عربي

Lebanese Offshore Oil & Gas Protection Framework

Introduction

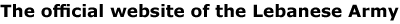

In March 2010, an estimate of the United States Geological Survey evaluated the unexplored potential reserves in the Levant Basin to 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and 122 trillion cubic feet of gas.2 These figures underscoring the basin’s potential to reshape regional energy dynamics, forms the foundation for understanding the stakes involved in offshore exploration, maritime boundary disputes, and energy security planning in the region. Following that, 2D and 3D seismic surveys conducted by two Norwegian companies, Spectrum and Petroleum Geo–Services, revealed something even more promising: Lebanon’s offshore potential was greater than that of neighboring countries. In just 3,000 square kilometers of Lebanese waters, they estimated around 25 trillion cubic feet of gas.3

While the results of seismic surveys and preliminary resource estimates are encouraging, it is crucial to underscore that such data indicate potential hydrocarbon presence rather than definitive proof. Seismic imaging, offers probabilistic insights but cannot confirm the existence or recoverability of reserves without exploratory drilling. Nonetheless, the magnitude of these findings holds strategic significance for Lebanon. Should commercial quantities be confirmed, the projected reserves are expected to satisfy domestic energy demands for decades, enable export opportunities, and generate substantial fiscal revenues. Consequently, the infrastructure supporting offshore exploration and transport—particularly drilling platforms and associated maritime assets— constitutes a vital strategic resource for the Lebanese state, warranting robust legal and security protections.

Nevertheless, along with the opportunities created by these discoveries in the sea and the potential for their extraction, there is a significant security risk to these drilling platforms. These offshore platforms could be located far from Lebanon’s shores and are targets for attacks and could have severe consequences for Lebanon, extending beyond the loss of life. Additionally, the economic damage caused by the halt in extraction until the infrastructure is rebuilt should also be considered. Such an attack could also have severe strategic implications, as it could cause significant damage to Lebanon’s energy supply.

The range of challenges faced by the drilling platforms is vast and includes the threat of explosive boats, land-to-sea missiles, guided air missiles, underwater sabotage operations, drones, and similar threats. Not only are the platforms themselves at risk, but also associated infrastructures, such as underwater pipelines, support vessels, and others. These challenges stem not only from their distance from Lebanon’s shores but also from the fact that the platforms are located in an area where Lebanon’s legal jurisdiction under international law is limited, primarily to the right to exploit natural resources. This reality poses a significant challenge for security forces, especially when dealing with ships with no prior intelligence indicating their involvement in hostile activity.

This article discusses the legal authority under international law to protect drilling platforms from terrorist attacks. It begins by outlining the relevant provisions and defining the basic terms necessary for legal analysis of the issue of jurisdiction. It then analyzes the legal means available to counter threats that do not rely on specific intelligence. Finally, the article proposes solutions to address the existing legal situation.

Chapter One

The regulatory framework for the protection of offshore petroleum installations

The international regulatory framework for the protection and security of offshore petroleum installations is supported by several key legal instruments that address the safety of offshore oil and gas operations. These include the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982, the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA) of 1988, and its associated Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Fixed Platforms on the Continental Shelf of 1988. Other significant instruments include the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) of 1974, the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code, the Revised Seafarers’ Identity Documents Convention of 2003, and the updated SUA Convention and Protocol of 2005. Additionally, within the context of Lebanon, Law No. 163, adopted in 2011, which delineates and declares the maritime zones of the Republic of Lebanon, forms a crucial part of the regulatory framework governing the protection of offshore installations in Lebanese waters. 5 Finally, UN Security Council Resolution 1701 (adopted in August 2006) ended the 2006 Lebanon War between Israel and Hezbollah. In the maritime domain, it authorized UNIFIL to assist the Lebanese Navy in monitoring territorial waters to prevent unauthorized arms shipments.

Section 1: The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Safety of Offshore Installations

Prior to examining the legal mechanisms through which UNCLOS enables coastal states to safeguard offshore petroleum installations, it is essential to establish a clear understanding of the Convention’s foundational principles and scope.

The laws of the sea broadly govern the legal rights and responsibilities of states concerning activities at sea. These laws, rooted in ancient customs, are codified in customary international law and treaties. The most prominent of these is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a comprehensive treaty signed in 1982 and entered into force in 1994, which defines states’ rights and responsibilities over maritime zones, navigation, natural resources, and the protection of the marine environment.

This convention has two fundamental principles relevant to our discussion. The first is the principle of flag state sovereignty, which holds that a vessel is under the sovereignty of the state in which it is registered. The flag state has exclusive legal authority over its vessels, except in specific cases explicitly regulated by the convention. This means that only the flag state has the authority to exercise sovereign powers over its vessels. The second principle is freedom of navigation, which guarantees that vessels from all states have complete freedom of movement on the high seas. Freedom of navigation can only be restricted in exceptional cases recognized by international law. Any infringement on a vessel's freedom of navigation without explicit authority under international law and without the flag state's consent may be considered an attack on the sovereignty of the flag state. In many cases, there is a tension between the freedom of navigation and a state's security needs.7

Lebanon acceded to UNCLOS through Law No. 295 (1994). Although Israel has not signed or ratified it, the provisions on maritime zones are widely recognized as customary law. In recent years, Lebanon has reinforced its sovereign rights over natural resources through domestic legislation, most notably Law No. 163 (2011).

Based on the general principles mentioned above, UNCLOS grants different powers and rights to states depending on the geographical area in question. In general, the scope of UNCLOS in regulating the protection of offshore installations is relatively narrow. Below, we will discuss Lebanon’s main maritime zones relevant to the current discussion where offshore platforms will be typically located.

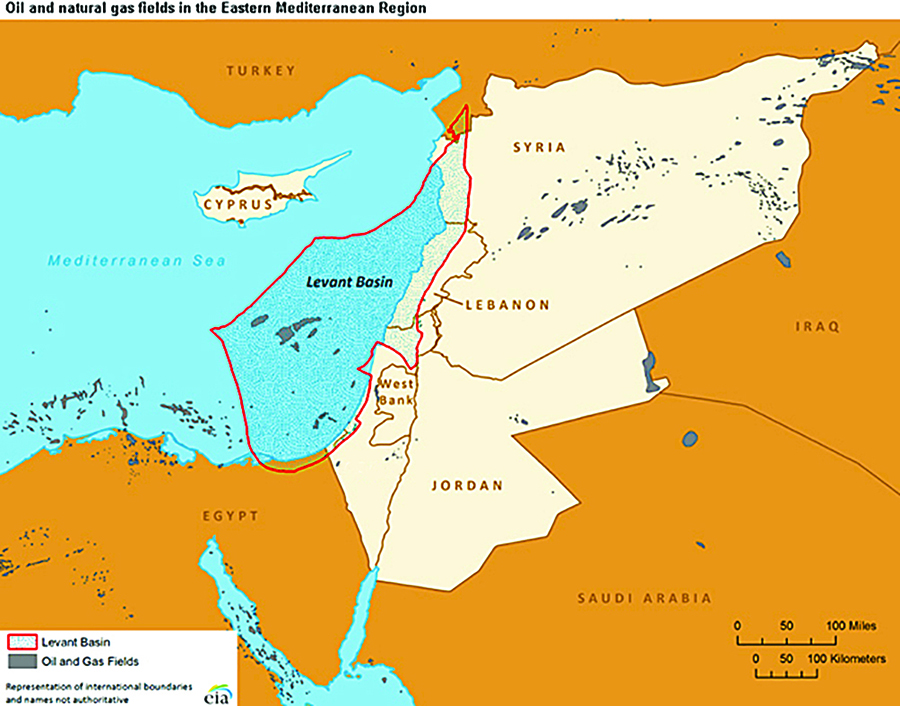

1. The Territorial Sea

Lebanon has established a 12 nautical mile (NM) territorial sea, which is a belt of water extending beyond its land territory and internal waters. Lebanon's sovereignty over this maritime area is equivalent to the sovereignty it exercises over its land territory, the airspace above and the seabed below, including the authority to impose navigation restrictions for security and safety reasons. However, foreign vessels are granted the right of "innocent passage" through this territorial sea,8 in accordance with Part II of the UNCLOS.

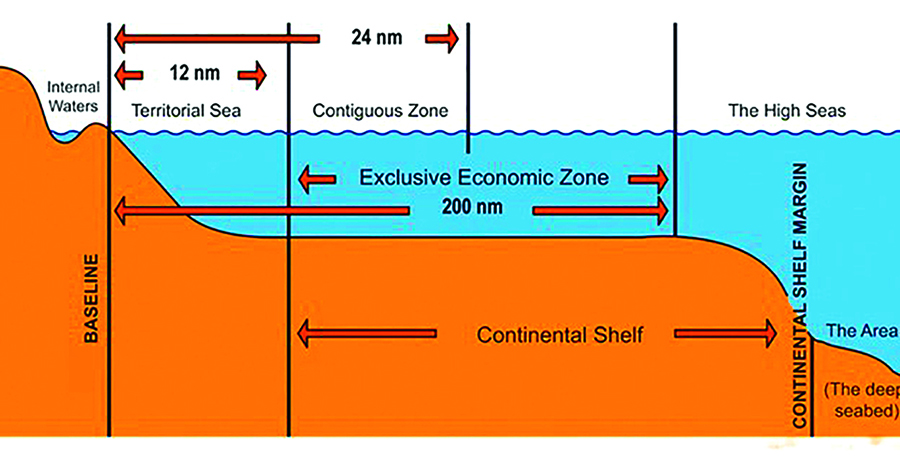

Within the territorial sea, Lebanon has extensive rights to implement various measures for safeguarding offshore installations. The Lebanese authorities designate sea lanes, enforce traffic separation schemes, and require foreign ships to adhere to them as shown in figure 3 below.

It is important to note that a country can temporarily suspend the innocent passage of foreign vessels in certain areas of its territorial sea if this is essential for its security or to prevent passage that is deemed non-innocent. Lebanon also has the authority to exercise criminal jurisdiction over foreign ships within its territorial sea, including arresting individuals on board if a ship has been involved in an attack on an offshore installation.

2. The contiguous zone

Lebanon also has the right to exercise control over a contiguous zone extending up to 24 NM from the baseline of its territorial sea.10 Within this zone, Lebanon can enforce its authority to:

a) Prevent violations of Lebanese laws and regulations related to security, customs, public health, fiscal matters, immigration, and pollution, whether these infractions occur within its land territory or territorial sea.

b) Impose penalties for breaches of these laws and regulations, regardless of whether the violations take place within its land territory or territorial sea.11

For purposes of oil and gas exploration and production, the contiguous zone as such has no unique significance for oil and gas, except insofar as it is the first part of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

3. The Continental Shelf (CS)

The concept of the Continental Shelf (CS) is primarily a legal one, rather than just a geographical feature. Despite having a narrow geographical continental shelf, Lebanon is entitled to a continental shelf that includes the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas extending beyond its territorial sea, up to a maximum distance of 200 NM from its baselines.12

Lebanon holds sovereign rights over this area for the exploration and exploitation of its natural resources, including mineral and non-living resources, as well as sedentary living organisms on the seabed and subsoil. These rights also cover activities such as drilling. Additionally, Lebanon has the exclusive right to construct artificial islands, installations, and structures for various purposes, including economic ones.13

No other state may exercise these rights within Lebanon's CS without the explicit consent of the Lebanese government. However, all states have the right to lay submarine cables and pipelines on the CS, though Lebanon reserves the right to establish the conditions for such activities and to control pollution.14

Notably, the CS does not require any form of occupation or explicit proclamation to be recognized.15

4. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

Lebanon has established an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This zone extends up to 200 nautical miles (NM) from the coastal baseline, as outlined in Part V of UNCLOS and Article 6 of Law No. 163.

Following Law No. 163, Decree No. 6433 was issued on October 1, 2011, delineating the EEZ boundaries.16 Lebanon formally notified the United Nations of this decree on November 16, 2011, marking a key step toward international recognition of its maritime claims. The EEZ, estimated at approximately 22,730 square kilometers, is strategically important due to its potential for oil and gas exploration.

Within its EEZ, Lebanon holds sovereign rights over the exploration, exploitation, conservation, and management of natural resources in the seabed, subsoil, and waters above. These rights also include economic activities such as energy production from water, currents, and wind. Lebanon has jurisdiction over artificial islands, installations, structures, and marine scientific research, and is responsible for protecting the marine environment and preventing pollution.

Article 56 of UNCLOS requires coastal and other states to show "due regard" for each other's rights—balancing economic interests with freedoms of navigation and overflight. While vessels in an EEZ are governed by their flag state, coastal states may enforce specific regulations, such as those related to fishing.

Lebanon’s EEZ remains open to all states for navigation, overflight, and laying cables and pipelines, provided these activities do not compromise its security. Additionally, Lebanon may establish zones for archaeological and cultural protection under the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, similar to other Mediterranean states that have declared fishery or ecological protection zones. 17

5. The high seas

The high seas are the areas of the sea that are not part of any state's EEZ or territorial waters. In the high seas, all states enjoy unrestricted freedom of navigation and overflight. Vessels on the high seas are subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the flag state. Lebanon does not have high seas within its maritime jurisdiction due to its geographic location and the relatively small expanse of its maritime zones in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The country is situated in a region where several countries have coastlines that are relatively close to each other, including Cyprus, Syria, and Israel. Because the Mediterranean Sea is narrow in this region, the maritime zones of these neighboring states often overlap or come close to each other.

Section 2: The 1988 Suppression of Unlawful Acts (SUA) and the 2005 SUA frameworks

In addition to SOLAS, two key frameworks contribute to the protection of offshore installations: the 1988 Suppression of Unlawful Acts (SUA) framework and its 2005 amendments.

1. The 1988 Suppression of Unlawful Acts (SUA) framework

The 1988 Suppression of Unlawful Acts (SUA) framework—comprising the Convention and its Protocol—was created to address violent offenses against offshore petroleum installations.19 It obligates state parties to criminalize such acts through domestic legislation and establish jurisdiction to prosecute them, even when committed beyond national boundaries.

Lebanon ratified the SUA Convention on April 7, 1999, thereby committing to its provisions for safeguarding maritime navigation and offshore infrastructure. This means Lebanon must recognize attacks on installations, such as oil platforms, as serious crimes under its national law, regardless of whether they occur in territorial waters or international zones.20 However, the framework has notable limitations. It covers fixed installations and mobile units in transit, but excludes mobile offshore installations actively engaged in operations like drilling or production. This gap could hinder Lebanon’s ability to respond legally if such a rig within its EEZ were attacked.

Additionally, the SUA framework does not authorize states to board foreign vessels or arrest individuals involved in violent acts against offshore installations. This restricts Lebanon’s capacity to act swiftly in cases of maritime terrorism originating from foreign-flagged ships.

Despite these constraints, the SUA framework remains a key element of international maritime security. It supports legal cooperation and enforcement, though Lebanon must complement it with robust national laws and additional agreements to fully protect its offshore resources.

2. The 2005 SUA framework

The 1988 SUA Convention and its 1988 Protocol were amended in 2005, resulting in the 2005 SUA Convention and the 2005 SUA Protocol.21 These amendments introduced three new categories of offenses: using a ship as a weapon or for committing terrorist acts, preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) on the high seas, and prohibiting the transport of individuals accused of offenses under other UN anti-terrorism conventions. While the scope of the 2005 SUA framework has generally expanded, the focus of these amendments did not extend significantly to offshore petroleum installations. As a result, the limitations and gaps identified in the 1988 SUA Convention and Protocol, particularly regarding enforcement and arrest powers, remain unaddressed in the 2005 versions. These gaps are especially pertinent when dealing with non-nationals or foreign-flagged ships.

Under both the 1988 and 2005 SUA frameworks, the motivation or purpose behind the offenders' actions is considered irrelevant. This means that the SUA framework can be applied to punish violent acts committed by perpetrators from various categories of offshore security threats, such as piracy, terrorism, insurgency, organized crime, vandalism, and even civil protest, provided the protest involves violence or the threat of violence. Additionally, internal sabotage, including the provision of sensitive or confidential information to perpetrators, falls under the SUA framework's scope.

The offenses covered by the SUA framework encompass a wide range of attack scenarios and tactics that perpetrators might use. These include bomb threats, the detonation of explosives or bombs, underwater attacks, the use of stand-off weapons, armed intrusion and seizure of an offshore installation, hostage-taking and kidnapping of offshore workers, using transport infrastructure as a weapon against an offshore installation, and the disclosure of confidential information that may assist in planning or carrying out an attack. Even attempted or unsuccessful attacks are within the framework's purview.

For a country like Lebanon, which faces various maritime security threats, the SUA framework provides a legal basis for addressing a broad spectrum of violent acts against offshore installations, even if there are still significant limitations in enforcement capabilities when foreign entities are involved.

Section 3. Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) is a key international maritime treaty that sets minimum safety standards in the construction, equipment, and operation of ships.22 Lebanon adhered to the SOLAS Convention in 1983 committing to its regulations and amendments over time.

In 2002, several security-related amendments were made to the SOLAS Convention, introducing new requirements for companies and ships. These included the implementation of ship security alert systems, granting masters discretion for ship safety and security, establishing control and compliance measures, and mandating the installation of an Automatic Identification System (AIS) on board ships.23 The AIS automatically provides information about a ship's identity, type, position, course, speed, and navigational status to other vessels and coastal authorities, enabling coastal states, including Lebanon, to monitor ship movements within their waters for security purposes. However, the SOLAS Convention does not require AIS to be fitted on offshore petroleum installations.

In 2006, the SOLAS Convention was further amended to include long-range identification and tracking (LRIT) provisions as a mandatory requirement for ships and mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs) engaged in international voyages24. These provisions apply to MODUs actively engaged in drilling operations on location and other types of mobile offshore installations, such as floating production storage and offloading units (FPSOs), although FPSOs are only required to comply with LRIT if they are considered ships when engaged in international voyages.

In alignment with its obligations under SOLAS, Lebanon established a Joint Rescue and Coordination Center (JRCC) at the naval base in Beirut.25 This center serves as the national hub for maritime search and rescue operations, coordinating responses to incidents within Lebanon’s maritime jurisdiction. Its operational mandate includes ensuring timely and effective assistance to vessels in distress, thereby fulfilling the requirements set forth in SOLAS Chapter V and the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR).26 The JRCC’s strategic location and integration with naval infrastructure enhance Lebanon’s capacity to manage emergencies and uphold international safety standards. The JRCC is equipped to handle distress signals, coordinate with other maritime agencies, and manage rescue efforts to safeguard lives and property at sea. The creation of this center aligns with Lebanon's commitment to enhancing maritime safety and fulfilling its international obligations under SOLAS.

Section 4. International Ship and Port Security (ISPS) code

The International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code is a comprehensive set of measures designed to enhance the security of ships and port facilities, developed by the IMO in response to the growing threats of maritime terrorism and other unlawful acts. The ISPS Code was adopted as an amendment to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in December 2002 and came into force on July 1, 2004.27

The ISPS Code establishes a standardized framework for evaluating and mitigating security risks to ships and port facilities. It is divided into two parts: Part A, which is mandatory, and Part B, which provides guidelines for implementation. The Code requires ships and port facilities to conduct security assessments, develop security plans, and appoint security officers responsible for implementing these plans. Additionally, it mandates specific security measures, such as access control, monitoring, and communication protocols, to prevent unauthorized access and ensure the safety of maritime operations.

The ISPS Code is also applicable to Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODUs) engaged on international voyages. However, the ISPS Code does not extend its provisions to fixed platforms, floating installations such as Floating Production Storage and Offloading units (FPSOs), Floating Storage and Offloading units (FSOs), or MODUs when they are on location. This limitation highlights a significant gap in the Code's coverage of offshore petroleum installations.

The ISPS Code's primary intent is to address the security of ships and port facilities, as reflected in its name. It suggests that contracting states 'should consider establishing appropriate security measures' for offshore installations that interact with ships and port facilities compliant with SOLAS and the ISPS Code. However, this recommendation lacks specificity. The term 'appropriate measures' is not clearly defined, and there are no detailed guidelines provided to assist states in developing and implementing security measures for offshore platforms and installations that fall outside the scope of the ISPS Code.

This gap means that while ships and port facilities are required to follow rigorous security protocols, offshore installations such as fixed platforms and FPSOs must rely on general security practices and national regulations that may not align with the same international standards. Consequently, states are left to determine and enforce their own security measures for these offshore facilities without a standardized framework or specific guidance from the ISPS Code.

Lebanon ratified the ISPS Code on August 22, 2005. This ratification aligned Lebanon with international maritime security standards, requiring its ships and port facilities to comply with the ISPS Code’s security measures. This commitment enhances the security of Lebanon’s maritime operations and facilities, although it does not extend directly to offshore installations like fixed platforms and floating units, which remain outside the ISPS Code's primary scope.

Section 5. Seafarers’ Identity Documents (SID) convention

The Seafarers’ Identity Documents (SID) Convention, adopted by the IMO in 2003, is a framework established to enhance maritime security by ensuring that seafarers are properly identified and vetted to prevent and deter the infiltration of the maritime workforce by terrorists and other adversaries, thereby protecting maritime operations from potential threats.28

The SID Convention mandates that all seafarers possess and carry identity documents that meet international standards. These documents must be issued by a competent authority and include biometric data to ensure authenticity. The rigorous verification process ensures that seafarers working on commercial ships, including tankers and offshore supply vessels, are properly vetted. This reduces the risk of malicious individuals gaining access to these vessels, which could otherwise be used in attacks on offshore installations.

Although the SID Convention does not specifically apply to identity documents for the offshore oil and gas industry, it indirectly contributes to the security of offshore petroleum installations. These installations often interact with various ships, such as tankers and offshore supply vessels, whose crew members are subject to the SID Convention's identity verification measures. By ensuring that seafarers are properly vetted and identified, the SID Convention reduces the risk of commercial ships being hijacked and used in attacks against offshore installations, thereby enhancing the overall security of the maritime industry.

Section 6. IMO's countervailing measures

To address the risk of collisions between ships and offshore installations, the IMO adopted several resolutions in the 1970s and 1980s related to offshore installations and navigational safety. Notably, Resolution A.671(16), Safety Zones and Safety of Navigation around Offshore Installations and Structures, provided recommendations on various measures to prevent infringements of safety zones around offshore oil and gas installations. However, this resolution did not grant coastal states any enforcement powers to address violations of these safety zones by foreign ships.29

The IMO utilizes ships' routing measures, including traffic separation schemes, recommended routes, and precautionary areas, to enhance navigational safety and protect offshore installations. These measures are outlined in the General Provisions on Ships’ Routing, which primarily focus on navigation safety and environmental protection. Proposals to implement these routing measures solely for security purposes are unlikely to gain IMO approval due to the organization's focus on safety and environmental considerations.

Offshore petroleum operations frequently occur in areas used by smaller vessels, such as fishing boats, offshore support vessels, and recreational crafts. These smaller vessels pose a threat to offshore installations but are not covered by the security requirements of the SOLAS Convention or the ISPS Code. To address this regulatory gap, the IMO adopted Non-Mandatory Guidelines on Security Aspects of the Operation of Vessels Which Do Not Fall Within the Scope of SOLAS Chapter XI-2 and the ISPS Code in 2008. However, these guidelines are not intended as a basis for regulating non-SOLAS vessels or related facilities.30

Chapter Two

Protecting Offshore Platforms with Engagement and Navigation Measures

The rules governing maritime security, particularly those established under the UNCLOS, provide mechanisms like the establishment of safety zones to protect these platforms. However, these measures are often limited in scope and may not fully address the complexities of modern threats.

This chapter explores the limitations of existing maritime rules, particularly the restrictions on the width of safety zones, and how they affect the ability to protect offshore installations. It examines what Lebanon can utilize to enhance the security of its offshore platforms, including the use of self-defense and the rules of war. The discussion also addresses the balance between ensuring security and maintaining freedom of navigation, a critical concern in international maritime law. Through this exploration, the chapter aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of operational strategies available to safeguard Lebanon's offshore oil and gas resources in an increasingly complex maritime environment.

Section 1. Creating Safe Zones Around Platforms Under Maritime Rules

International maritime law permits coastal states to establish safety zones around offshore exploration platforms, particularly within their territorial seas. In these waters, states possess broad regulatory authority to implement protective measures, including the delineation of exclusion zones surrounding oil and gas installations. Such authority encompasses the regulation of innocent passage, maritime traffic, and the maintenance of navigational infrastructure.

Beyond the territorial sea, however, the legal capacity of coastal states—such as Lebanon—to safeguard offshore petroleum infrastructure located within the EEZ and on the continental shelf is significantly constrained. UNCLOS authorizes coastal states to establish safety zones around installations in the EEZ, but restricts their maximum radius to 500 meters.31 While UNCLOS stipulates that these zones must be proportionate to the nature and function of the installation, it does not elaborate on the permissible scope of protective actions within them. This regulatory ambiguity, coupled with the limited spatial coverage, renders such zones inadequate for countering contemporary security threats, including deliberate hostile acts by large vessels.

UNCLOS also lacks explicit provisions empowering coastal states to interdict or board foreign vessels suspected of engaging in attacks or unlawful interference with offshore installations in the EEZ or on the high seas. The convention’s emphasis on preserving navigational freedoms and exclusive flag state jurisdiction further complicates enforcement efforts. Although piracy is addressed within the UNCLOS framework, its applicability to fixed offshore platforms is narrowly confined to instances where the installation is legally classified as a ship during the attack.

Historical Development of the 500-Meter Limit

The origin of the 500-meter safety zone traces back to the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf. Archival research reveals that this distance was adopted from terrestrial fire safety standards used to protect onshore oil facilities, without consideration of maritime-specific risks such as high-speed vessel collisions or terrorism. During the UNCLOS negotiations in the 1970s, several states advocated for a more flexible approach, proposing that coastal states be allowed to determine zone widths based on operational needs. These proposals were ultimately rejected due to concerns over potential encroachments on navigational freedoms, resulting in the retention of the 500-meter cap.32

UNCLOS does provide a mechanism for extending safety zones beyond this limit, contingent upon recommendations from a competent international organization—namely, the International Maritime Organization (IMO). However, the IMO has consistently denied such requests, including Brazil’s 2007 proposal for a 1,400-meter zone, citing insufficient justification and apprehensions about setting a precedent that could restrict global maritime mobility.33

Operational and Security Limitations

The practical utility of the 500-meter safety zone is limited. It functions primarily as a navigational buffer, lacking the infrastructure and legal clarity necessary for robust enforcement. Intrusions by unauthorized vessels or individuals pose both safety and security risks, yet the response capabilities within such a narrow perimeter are severely constrained. For instance, a vessel traveling at 25 knots can traverse the zone in approximately 40 seconds—an interval too brief for effective threat assessment, communication, and interception.

Moreover, the zone’s design prioritizes accident prevention rather than defense against intentional attacks. It does not accommodate the spatial requirements for intercepting large vessels or mitigating threats posed by modern weaponry capable of striking from beyond the zone’s boundary. The absence of IMO-approved extensions further exacerbates this vulnerability.

Although UNCLOS permits the establishment of broader zones under generally accepted international standards, the IMO’s reluctance to endorse such measures—especially for security purposes—reflects enduring geopolitical sensitivities. In practice, coastal states have increasingly invoked national security doctrines and customary international law to justify expanded maritime jurisdiction post-9/11. The inherent right of self-defense remains a foundational principle, offering a potential legal basis for protective actions beyond the limitations of UNCLOS.

In conclusion, the current international legal framework does not adequately address the evolving threat landscape surrounding offshore petroleum installations. The spatial and jurisdictional constraints imposed by UNCLOS, coupled with the IMO’s conservative stance on zone expansion, necessitate a reevaluation of Lebanon’s strategic options under self-defense principles and the laws of armed conflict to ensure the security of its offshore assets.

Section 2: Safeguarding Installations through Self-Defense

The right of self-defense is another mechanism Lebanon can utilize to safeguard its valuable maritime assets. This approach enables the country to protect its interests while navigating the complexities of international legal and security frameworks.

The right of self-defense, as articulated in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, is a fundamental principle in international law that permits a state to use force in response to an armed attack. This right is a notable exception to the general prohibition on the use of force between states, which is enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter.35

Article 51 originally focused on responses to attacks by other states. This traditional interpretation aligns with the state-centric nature of the UN Charter, which was drafted in the aftermath of World War II to prevent inter-state wars. However, contemporary interpretations and state practices have expanded its application to include responses to attacks by non-state actors, such as terrorist organizations. This shift has been driven by the rise of transnational terrorism and other forms of non-state aggression. In addition, modern international law also acknowledges the right of states to use force not only in response to actual attacks but also to prevent imminent threats. This concept of preventive self-defense allows a state to act preemptively if an armed attack is imminent and unavoidable, even if it has not yet occurred. This interpretation seeks to address situations where waiting for an attack to materialize could result in catastrophic consequences.

For the use of force under the right of self-defense to be legally justified, it must meet three cumulative conditions:

1. Necessity (Exhaustion of Non-Violent Means): The necessity requirement dictates that force should only be used when non-violent measures have been exhausted or are not feasible under the circumstances. States must first attempt to resolve the threat through diplomatic, economic, or other peaceful means before resorting to armed force. This principle ensures that force is a last resort.

2. Proportionality (Appropriate Response): The proportionality requirement ensures that the level of force used is commensurate with the nature and scale of the attack. The response must be adequate to repel the attack or prevent further harm but should not exceed what is necessary to achieve these objectives. The force used should be limited to what is needed to address the immediate threat without causing excessive collateral damage or escalation.

3. Immediacy (Timely Response): The immediacy requirement pertains to the timing of the response. Force may only be used to counter threats that are imminent and expected to materialize in the near future. This condition ensures that preemptive actions are justified and not based on speculative or distant threats. The intent is to prevent harm by addressing imminent risks before they escalate into actual attacks.

Section3. The Rules of War at Sea

The conduct of military operations at sea during armed conflict is governed by a body of rules commonly referred to as the law of naval warfare. These rules, though not codified in a single binding treaty, have evolved primarily through customary international law and are consolidated in the San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea (1994).36 The Manual serves as a comprehensive guide to operational principles, behavioral norms, and emerging trends in maritime conflict regulation.

While traditionally shaped by inter-state warfare, the San Remo Manual affirms that the powers granted to states under the law of armed conflict at sea may also be exercised in confrontations involving non-state actors, including terrorist organizations.37 This is particularly relevant in the context of Lebanon, which—since gaining independence in 1943—has occupied a volatile geopolitical position in a region marked by recurrent hostilities. The establishment of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent regional tensions have frequently drawn Lebanon into military engagements, including operations at sea. The rise of non-state threats has further complicated Lebanon’s security landscape, necessitating robust maritime defense measures.

Under the principles articulated in the San Remo Manual, a state engaged in armed conflict may impose navigation restrictions not permissible during peacetime and may use force against vessels that violate these restrictions or pose a credible threat.38 Such measures include the enforcement of blockades, vessel inspections, and, where necessary, military action to neutralize hostile actors. In Lebanon’s case, these powers are essential for safeguarding offshore infrastructure and maritime borders against terrorist threats.

In scenarios where a vessel approaches an offshore platform with credible intelligence suggesting an imminent attack, the use of force may be legally justified under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, which enshrines the right of self-defense.⁵ However, actionable intelligence is not always available in advance, underscoring the importance of early threat detection and extended response time.

International law permits coastal states to impose temporary navigation restrictions beyond the standard 500-meter safety zone, provided such measures are justified by active hostilities or imminent threats.39 These restrictions must be carefully calibrated to avoid infringing on the territorial waters of uninvolved states and should minimize disruption to international navigation, recognizing that even lawful measures may attract diplomatic scrutiny.

One of the most significant instruments available to states during armed conflict is the declaration of an exclusion zone, which prohibits entry by foreign vessels for reasons of military necessity.40 Though controversial, exclusion zones are recognized under the San Remo Manual as lawful when they meet specific conditions. Their scope and enforcement must be proportionate to the military objective, notification must be issued to non-combatant states, detailing the zone’s parameters and enforcement protocols, and access to neutral ports must remain unobstructed, preserving the rights of uninvolved states.

Historical precedent, such as the United Kingdom’s 200 NM exclusion zone during the Falklands War, illustrates both the strategic utility and diplomatic sensitivity of such declarations.41 In Lebanon’s context, exclusion zones or similar restrictions may be justified if combat operations near offshore platforms are necessary to prevent hostile actions. However, these measures must be implemented with precision and transparency to avoid arbitrary enforcement and to uphold international legal standards.

Conclusion

Protecting offshore drilling platforms is a significant challenge for Lebanon, particularly given the complexities of international law concerning navigation restrictions within EEZs where these platforms could be located.

When a state has credible, evidence-based information about a vessel's intent to attack a drilling platform, it is granted considerable authority to act under the principles of self-defense or the laws of war to neutralize the threat. However, addressing general threats—those not supported by specific intelligence—is a more formidable challenge. While maritime law does allow the state to establish safety zones around platforms and restrict vessel access, these zones are limited to a maximum of 500 meters from the platform. This distance is insufficient to provide security forces with adequate time to respond to potential threats.

The principles of self-defense and the laws of war do permit the imposition of navigation restrictions beyond the 500-meter limit, which could extend response time and enhance the ability to counter threats to the platforms. However, these legal provisions are typically limited to situations involving an imminent threat or ongoing combat near the platforms, offering little support for routine protection when no immediate danger is present.

Lebanon's challenge in legally safeguarding its drilling platforms from terrorist attacks is not unique. A more comprehensive legal solution would require international cooperation, potentially leading to amendments in maritime regulations to allow for safety zones larger than 500 meters or, at the very least, to draft recommendations to the IMO for the expansion of these zones. However, such a solution is unlikely to be realized in the near future, necessitating that states explore practical measures for protecting their platforms within the current legal framework.

One practical approach is the use of "soft" protection methods, such as questioning vessels that enter the vicinity of the platforms and establishing "warning zones." While these measures may help in identifying potential threats, their effectiveness could diminish over time without sustained international cooperation. Developing an international cooperation system in this field could help maintain the effectiveness of these methods, though achieving such cooperation may be less challenging than securing global agreement on expanding safety zones around drilling platforms.

References

1. Doswald-Beck L (ed), San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

2. McCoubrey H and Morris M, Regional Peacekeeping and International Enforcement: The Falklands Conflict and the Law of War, Dartmouth Publishing, United Kingdom, 1997.

3. Rothwell Donald and Stephens Tim, The International Law of the Sea, Bloomsbury Publishing, United Kingdom, 2016.

Websites and Online Documents

1. British Admiralty Nautical Chart 8178, Port Approach Guide Beirut, UK Hydrographic Office https://mdnautical.com/home/21105-british-admiralty-nautical-chart-8178-port-approach-guide-beyrouth-beirut.html,.

2. Charter of the United Nations. http://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chaptervii/index.html.

3. Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA), adopted 10 March 1988, entered into force 1 March 1992, 1678 UNTS 201 <1988-Convention-for-the-Suppression-of-Unlawful-Acts-against-the-Safety-of-Maritime-Navigation-1.pdf>.

4 Decree No. 6433 dated 1 October 2011 on the Delineation of the boundaries of the exclusive economic zone of Lebanon, notified to the United Nations on 16 November 2011 http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/lbn_2011decree6433.pdf.

5. Fattouh B and El-Katiri L, Lebanon: The Next Eastern Mediterranean Gas Producer? Oxford Institute for Energy Studies 2015, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/lebanon-the-next-eastern-mediterranean-gas-producer/.

6. ICRC, International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts (2015) https://www.icrc.org/en/document/international-humanitarian-law-and-challenges-contemporary-armed-conflicts.

7. IMO Resolution A.671(16), Safety Zones and Safety of Navigation around Offshore Installations and Structures https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/Knowledge Centre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.671(16).pdf,

8. Inauguration of the Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC) at the Beirut Naval Base, 1 October 2025 https://www.lebarmy.gov.lb/en/content/inauguration-joint-rescue-coordination-center-jrcc-beirut-naval-base.

9 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), adopted 1 November 1974, entered into force 25 May 1980 <International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974.

10. International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR), adopted 27 April 1979, entered into force 22 June 1985 <International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR).

11. International Labour Organization, Convention Concerning Seafarers’ Identity Documents (Revised), 2003 (No. 185), adopted 19 June 2003, entered into force 9 February 2005 <Seafarers' Identity Documents Convention (Revised), 2003 : ILO Convention No. 185 - International Labour Organization>,

12. International Maritime Organization, MSC.1/Circ.1283 – Non-Mandatory Guidelines on Security Aspects of the Operation of Vessels Which Do Not Fall Within the Scope of SOLAS Chapter XI-2 and the ISPS Code (22 December 2008) <MSC.1/Circ.1283 Non-Mandatory Guidelines>,

13. International Maritime Organization, Report of the Maritime Safety Committee on its 87th Session, IMO Doc MSC 87/26/Add.1, 2009

14. International Maritime Organization, SOLAS Amendments 2002: Adoption of the ISPS Code, IMO Doc MSC/7 (2002) <Amendments to the Annex to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, including the ISPS Code>,

15. International Maritime Organization, SOLAS Regulation V/19-1: Long-Range Identification and Tracking of Ships, IMO Doc MSC.202(81), adopted 18 May 2006 <Long-range identification and tracking (LRIT)>,

15. International Maritime Organization (IMO), International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code, adopted as part of SOLAS Chapter XI-2 by resolution MSC.134(76), December 2002, entered into force 1 July 2004, SOLAS XI-2 and the ISPS Code.

16. Lebanese Official Gazette, Law No. 239 – Ratification of the SUA Convention, published 7 April 1999.

17. Marine Public, Offshore: The 500M Safety Zone & Marine Operations Safety,2024, https://www.marinepublic.com/blogs/offshore/924693-offshore-the-500m-safety-zone-marine-operations-safety.

18. Marine Safety Forum, Marine Operations: 500m Safety Zone Guidance, 2018, https://www.marinesafetyforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Marine-Operations-500m-zone-guidance.pdf.

19. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department of Commerce, 2018 www.noaa.gov.

20. Napang M and others, ‘Safety Zones Around Offshore Installations , 2019,(2) Journal of Global Cooperation https://journal.riksawan.com/index.php/IJGC-RI/article/ download/39/35/

21. Protocol of 2005 to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, IMO Doc LEG/CONF.15/21 ,2005 Protocol_to_Maritime_Convention_E.pdf.

22. U.S. Energy Information Administration, Overview of Oil and Natural Gas in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 15 August 2013, available at https://www.eia.gov/ international/content/analysis/regions_of_interest/Eastern_Mediterranean/eastern-mediterranean.pdf.

23. United States Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Levant Basin Province, Eastern Mediterranean, Fact Sheet 2010–3014 (March 2010) https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/fs20103014.

الإطار التنظيمي لحماية موارد النفط والغاز في لبنان

العميد الركن جورج درزي

تتناول هذه الدراسة الإطار القانوني والأمني لحماية منشآت النفط والغاز البحرية اللبنانية، بالاستناد إلى القانون الدولي للبحار والتشريعات الوطنية والبروتوكولات العسكرية. ومع وجود ما يُقدّر بـ25 تريليون قدم مكعب من الغاز في المياه اللبنانية، تبرز أهمية استراتيجية لهذه الموارد في تعزيز أمن الطاقة والتنمية الاقتصادية. يستعرض هذا المقال الوضع القانوني المزدوج للمنشآت البحرية، ويُبرز الثغرات في الحماية ضمن المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة كما يُقيّم التزام لبنان بالاتفاقيات الدولية مثل اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار واتفاقية قمع الأعمال غير المشروعة واتفاقية سلامة الأرواح في البحار، ومدونة أمن السفن والمرافق المينائية، مع التركيز على محدودية التنفيذ واتساع نطاق الحماية. وتُحلّل الدراسة القوانين اللبنانية، ومنها القانون الرقم 163/2011 والمراسيم 6433/2011 و42/2017، في رسم الحدود البحرية وتنظيم عمليات الاستكشاف. كما تُبرز أهمية القرار 1701 الصادر عن مجلس الأمن، وتناقش تطور مفهوم الدفاع المشروع في القانون الدولي، لا سيما في مواجهة التهديدات غير الحكومية. وتخلص الدراسة إلى ضرورة تعزيز التنسيق الوطني والتعاون الدولي، واعتماد نهج أمني متعدد المستويات يجمع بين الالتزامات القانونية والواقع العملياتي لحماية الثروات البحرية اللبنانية.