- En

- Fr

- عربي

Offshore balancing in the American strategic culture, an alternative strategy for the Middle East

“The time to think about alternative grand strategies is now – before the United States is overtaken by event”- Christopher Layne

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to outline why the US should abandon its current hegemonic strategy and adopt one centered on offshore balancing. This is not a new concept, it traces its roots in the American thalassocracy culture inspired by ancient writings and doctrines. This paper will clarify how the US exploit the country’s providential geographic position to balance against powerful neighbors. In this context, offshore balancing is an amphibious concept which should be linked with onshore access.

This article describes the two principal reasons why the Eurasian pivot should play a central role in the American doctrine. Offshore balancing strategy can break up alliances directed against the US and counter potential hegemons. The Middle East is a vital region for American interests. More than ever, the debates surrounding the durability of American hegemony in this region are a hot topic. It will analyze how the US needs to revamp its regional Grand Strategy as it seems inadequate to the actual context. By doing so, it is an approach to adapt the containment strategy to prevent the “rise of the rest” in the Middle East.

In order to address this topic, the first part will present analysis on why offshore balancing cannot be disassociated with onshore access. The second section will discuss how offshore balancing can be considered as an alternative strategy for the Middle East.

Offshore balancing and onshore access

The interest of America in Sea Power

The offshore balancing finds its roots in the geographical positioning of the United-States. The large coastlines providing unprecedented access to both the Pacific and the Atlantic led Mackinder to note how the US is an insular crescent similarly to Japan and Great-Britain. These large expanses of water, however, are viewed as both a threat and an opportunity. As the French geographer Max Sorre stated: “insularity means isolation, refuge, withdrawal, the scorn of others and conservative characters. It also means a call from the sea, the sense of adventure and a boost to expand power”[1]. In this philosophical context, the US decided to exploit its geographical advantage shortly after the Treaty of Paris, which formally granted independence to the new country. In 1784, The Empress China, the first American merchant ship, linking Shanghai to New York marked a new beginning that led the US to wave its flag on all maritime surfaces. Not taking into consideration the oscillations of their foreign policy - between diplomatic isolationism and interventionism – the offshore access to other continents has always been a crucial necessity for the US. In other words, it is considered to be a strategic variable relatively independent from diplomatic doctrines that influence American foreign policy[2].

This leads the way to the texts of the Admiral A. Mahan, a disciple of Sea Power via his doctrine published in 1897 - The interest of America in Sea Power. He stands out as one of the foremost thinkers on naval warfare and maritime strategy. Mahan also impacted the world of International Relations and strategic affairs. In his theory, he saw the US as the geopolitical successor of an enfeebled British Empire. In Mahan’s day, Britain was viewed as the leading world power. “Today, it is difficult even to imagine the magnitude of the British Empire. At its height, it covered about a quarter of the earth’s land surface and included a quarter of its population. London’s network of colonies, territories, bases, and ports spanned the globe”[3]. This leadership on the international system rested on Britain’s financial power, vast colonial empire and manufactures. But this position was threatened by other great powers aspiring to take the lead. Mahan feared the decline of the British Empire, as the American security was linked to it. This relationship can be explained by the term “complex interdependence” (it is the idea put forth by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye believing that states and their fortunes are inextricably tied together).

In his perspective, he believed that national greatness was predicated on the sea. Mahan concluded that war and change in world politics was rooted in competitions among the great powers, which struggled for security, wellbeing and leadership. He contended that the great commercial seafaring states in particular would play a leading role in world politics because of the wealth they generated from international trade[4]. According to his conviction, the US had to capitalize on the sea’s commercial significance during times of peace and its control during times of war. In fact, he compared the oceans to “highways” that had two main repercussions on the US. The foremost was considered as an advantage as sea access allowed the US to strengthen its ties with the rest of the world. The second was seen as a weakness since access to the world is a two-way street and threats to continental soil were more likely (for example Pearl Harbor in 1941).

A geopolitical destiny

The US has, therefore, a geopolitical destiny[5] in light of its geographical position. In this context, Washington found it necessary to become a maritime and naval power before the oceans were controlled by others. In fact, Mahan feared Imperial Russia, a challenger to Britain to take the lead on the international scene. He firmly believed that a show down could occur between Britain (the sea power) and Russia (the continental state). He “feared that an expansionist Russia would take control of an enfeebled China, and Britain would have difficulty stopping this Russian advance on the Eurasian mass”[6], stretching from Europe, through the Middle East, to China and Northeast Asia. In fact, in the middle of the 19th century, Britain and Russia had fought in a major conflict, the Crimean War – the so called “Great Game”. But Russia’s defeat didn’t mean the end of Grand Britain’s difficulties. Instead, Germany’s rise as a great naval power, along with Japan’s success over Russia increased Mahan’s concern about the balance of power in Europe and Asia. “These coming struggles were likely to produce dramatic shifts in the power balances among the great powers”[7]. They could have a considerable impact on the security of the United States. He tried to highlight how the emerging geopolitical threats to Britain’s role also posed a danger to the American security. Therefore, Mahan argued that the United States should not only align itself with Britain, but with Germany and Japan as well forming the bloc of “sea powers”. In fact, the United States had to play a more active role in the international system to support Britain’s position. Therefore, offshore balancing could be defined as such: “offshore balancing is a grand strategy born of confidence in the United States’ core traditions and a recognition of its enduring advantages. It exploits the country’s providential geographic position and recognizes the powerful incentives other states have to balance against overly powerful or ambitious neighbors”[8].

Mahan’s observations are still relevant nowadays. In an internal speech to the Central Military Commission in July 2013, President Xi Jinping made a clear link between sea power and influence in word politics: “in the 21st century, mankind has entered the age of the large-scale exploitation of the sea… History and experience tell us that a country will rise if it commands the oceans well and will fall if it surrenders them. A powerful state possesses durable sea rights, a weak state has vulnerable sea rights… We (China) must adhere to a development path of becoming a rich and powerful state by making use of the sea”[9]. President Xi Jinping sounds like being a committed disciple of Mahan’s school of sea power. Robert Kaplan writes: “tellingly, whereas the US Navy pays homage to Mahan by naming buildings after him, the Chinese avidly read him; the Chinese are the Mahanians now”[10].

Onshore access: the theory of naval-base

However, Mahan was not only a defendant of “Sea Power”, but also developed the doctrine of the “theory of naval-base”. This doctrine based itself on the notion that “Foreign military bases have been established throughout the history of expanding states and warfare. They have proliferated, though, only where a state has imperial ambitions, that is, where it aspires to be an empire, either through direct control of territory or through indirect control over the political economy, laws, and foreign policy of other places”[11]. Mahan focused on the importance of geographical positioning through the acquisition of bases. His theory is in fact inspired from England’s experiences. As he stated in his book, The influence of Sea Power upon History (1660-1783): “England’s naval bases have been in all parts of the world; and her fleets have at once protected them, kept open the communications between them, and relied upon them for shelter”[12]. This led to the extension of American naval power to strategic locations such as chokepoints and to coasts all around the world. In fact, military bases fulfill several strategic roles: supplying other allies’ nations with security, and controlling trade and resources. “Bases are the literal and symbolic anchors, and the most visible centerpieces, of the US military presence overseas”[13]. As we noticed, the US are building an “empire of bases” that is associated with “a growing gap between the wealth and welfare of the powerful centers and the regions affiliated with it”[14]. Therefore, the US are creating a “military diplomacy” to increase their influence. This strategic thinking will be taken over by Raoul Castex in his book Théories Stratégiques.

The offshore balancing is an amphibious and complex notion, anchored in the American geopolitical culture. The American vision to expand their power lies in the association between offshore balancing and onshore access. This strategy established the link between offshore balancing and the development of naval and maritime assets. However, this consideration should be questioned with the development of Anti Access/Area Denial weapons (A2/AD). Denying access to certain regions around the world compels the US to find different means to reach a geostrategic zone. De facto, the rise of state competitors with new A2/AD technologies forces the American thalassocracy to question their naval doctrines.

The offshore balancing as an alternative strategy for the Middle East

The failure of the US Grand Strategy

The emerging international system is likely to be quite different from those that have preceded it. As Fareed Zakaria stated in his article “The future of American Power” published in Foreign Affairs, world politics knew three shifts over the last 500 years reshaping international life (politics, economics and culture). The first one was the rise of the Western world between the 15th and 18th century. The second change was the rise of the United States in the 19th century. The US dominated global economics, politics, science, culture and ideas. That dominance has been unprecedented in history. In fact, the distribution of power is shifting, moving away from the US dominance. “We are now living through the third great power shift of the modern era- the rise of the rest”[15]. We are moving into a “post-American world” where the “rise of the rest” is constantly noticed. If Mahan was writing today, he would certainly warn about the shifting global balance of power. Those shifts in the international system resemble Britain’s declining power position at the beginning of the 20th century. “Britain was undone as a global power not because of bad politics but because of bad economics”[16] while the American decline can be explained by a highly dysfunctional politics especially in foreign policy.

“Grand strategy can be understood simply as the use of power to secure the state”[17]. Following the American intervention in Iraq and the chaos installed in the Middle East, the US needs to revamp its regional Grand Strategy because it seems inadequate. It is also a reminder that Wilsonianism is not always the best answer. This concept comes from the ideas and proposals of President Wilson and especially his famous Fourteen Points (January 1918) for promoting world peace and inspiring liberal internationalism. This doctrine argues that liberal states should intervene in other sovereign states in order to pursue liberal objectives. The Middle East is no exception to the offshore balancing strategy. “In essence, the aim is to remain offshore as long as possible, while recognizing that it is sometimes necessary to come onshore”[18]. Broadly speaking, the central goal of this strategy is to prevent the emergence of a dominant power in Europe and East Asia; a Eurasian hegemon that could cause an existential threat to the US. In other words, this strategy seeks to maintain US hegemony in Western hemisphere while preserving a balance of power in geo-strategically important regions. This belief was the basis for Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. Those policies would eventually establish the US as the only great power in the Western Hemisphere. In fact, “by expanding across North America and driving the European powers out, the United States was able to keep dangerous adversaries at a distance, thereby maximizing its own security and freedom of action”[19].

Heretofore, the US, as an insular great power, seeks to use this inherent strategic advantage for the offshore balancing strategy. The insularity can be summarized into two advantages. Firstly, their allies in the region will help them contain the rising powers. Secondly, if they should get involved, they are protected by geography and their own capabilities present within their military bases. “However, beyond these traditional advantages of insularity, offshore balancing does – or can – have a wedge strategy dimension”[20]. The goal for great powers behind this strategy is the same: increase the state’s relative power by preventing hostile alliances or dispersing those that have formed. It induces potential balancers to buck-pass bandwagon or to hide it. This strategy can be defensive or offensive. First, “the divide and balance” wedge strategies are a response to a threat, especially when the state is challenged by a likely or an actual coalition of enemies. Second, a state could use offensive wedge strategies to break up anticipated or actual counterbalancing alliances[21]. Wedge strategies – whether defensive or offensive – aim to increase the state’s relative power by preventing opponents to form threatening alliances. The Bush administration’s Middle East policy was a perfect illustration of an anti-wedge strategy. Rather than preventing the coalescence of enemies threatening the US, the Bush strategy in contrario unified diverse groups against American interests. In fact, “an offshore balancing strategy would break sharply with the Bush administration’s approach to the Middle East. As an offshore balancer, the US would redefine its regional interests, reduce its military role, and adopt a new regional diplomatic posture”[22]. It would seek to reduce the terrorist threat by limiting US military presence in the region, and to suppress the anti-American feeling in the region by pushing for a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Israeli-Arab conflict). This strategy aims to avoid a further destabilization of the Middle East. As an offshore balancer, the US would try to find a diplomatic agreement despite its differences with Iran.

From Think Tanks to foreign policy real world

The decade 2000 marked by military interventions promoting nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan enabled the Obama administration to find – at least theoretically – a point of balance between maintaining the American leadership in international affairs and its possible disengagement from regional conflicts[23]. After emerging in the US academic debate in the nineties, the concept of offshore balancing gained traction during the Obama presidency. It was theoretically born in the American think tanks such as the Center for a New American Security. This concept emerged and fits into the American debate on the politico-military doctrine to adopt after the Cold war.

The initial promoter, Christopher Layne, professor at the Naval Postgraduate School of Monterey, published an article in 1997 in the International Security journal in which he stated: “An offshore balancing strategy would have two crucial objectives: minimizing the risk of U.S. involvement in a future great power (possibly nuclear) war, and enhancing America’s relative power in the international system. Capitalizing on its geopolitically insular position, the United States would disengage from its current alliance commitments in East Asia and Europe. By sharply circumscribing its overseas engagement, the United States would be more secure and more powerful as an offshore balancer in the early twenty- first century than it would be if it continues to follow the strategy of preponderance”[24].

This concept program suggests to maintain the American supremacy while keeping the country away from regional conflicts and power games (Middle East, Europe and Asia). Offshore balancing could therefore be able to combine the advantages of isolationism and interventionism while putting aside their disadvantages. The White House also adopted this concept program when publishing the expression in spring 2011 “leading from behind”. Broadly speaking, this expression also means offshore balancing. While supporting the French and British forces against the regime of Gadhafi and without leading the operation, the US can indirectly benefit from the success of the mission.

Therefore, the quasi-triumph of the offshore balancing is embodied in the Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG) in 2012 as Christopher Layne states in January 2012 in the journal National Interest. This official document shows the will of the Obama Administration to cut down military spending and the number of their overseas forces due to the fiscal and economic constraints. It also “reflects the reality that offshore balancing has jumped from the cloistered walls of academe to the real world of Washington policy making”[25]. Offshore balancing proponents agree on common strategic principles that will therefore affect the American posture in the Middle East:

- The offshore balancing strategy is adapted to the American politico-military doctrines and geopolitical culture. In fact, America’s strategic advantages mainly rest on naval and air power, not on sending land armies to fight ground wars in Eurasia. Therefore, the US should opt for the strategic percepts of Alfred Thayer Mahan over those of Sir Halford Mackinder: the primacy of air and sea power over land power. Mahan’s percepts are definitely anchored in the American strategic culture.

- By reducing its geopolitical and military footprint on the ground in the Middle East, the US will reduce the anti-American feeling and the incidence of Islamic fundamentalist terrorism directed against them.

- Offshore balancing strategy will allow the US to avoid future large-scale-nation-building operations like those in Iraq and Afghanistan which are considered to be a failure. It will also refrain from fighting wars for the purpose of establishing democracy.

- As Layne stated: “offshore balancing is a strategy of burden shifting, not burden sharing. It is based on getting other states to do more for their security so the United States could do less”[26].

Offshore balancing is implicitly mentioned in the DSG: “where possible, we will develop innovative, low-cost, and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives, relying on exercises, rational presence, and advisory capabilities”[27].

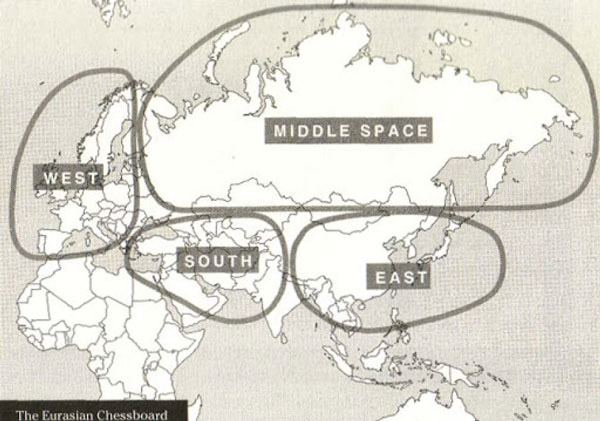

Neo-containment: a strategy towards “the rise of the rest”

The Eurasian chessboard for Z. Brzezinski is oddly shaped, extending from Lisbon to Vladivostok[28] where the “game” for global primacy could be played. It is divided into four regions: middle space, east, south, and west. “Eurasia is the globe’s largest continent and is geopolitically axial. If we look at the Eurasian chessboard, we notice that it also refers to the concept of Rimland[29] as described by Nicholas Spykman. The control of Eurasia and Africa (The World Island)[30] is achieved via the control of countries bordering the ex-Soviet Union. A power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world’s three most advanced and economically productive regions. A mere glance at the map also suggests that control over Eurasia would almost automatically entail Africa’s subordination, rendering the Western Hemisphere and Oceania geopolitically peripheral to the world’s central continent”[31].

If we refer to it, we notice that the Middle East is part of its south. Brzezinski’s well-known analysis explains briefly the American posture vis-a-vis the Eurasian pivot: “If the middle space can be drawn increasingly into the expanding orbit of the West (where America preponderates), if the southern region is not subjected to domination by a single player, and if the East is not unified in a manner that prompts the expulsion of America from its offshore bases, America can then be said to prevail”[32].

Therefore, the United States should impose themselves as a main player to contain the influence of rival powers on this chessboard and particularly in the Middle East. The geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States was constantly reshaped. From the beginning of the Cold war and till nowadays, Middle East politics were impacted by the upheavals of the American strategy. From containment to neo-containment passing through dual containment (Iraq and Iran), the Middle East region is the theater of indirect confrontations between regional and international great powers. The term “neo-containment” emerged in the mid-1990s to denote a more modern and nuanced version of strategic (Cold War) containment. It is a series on mini-containments in response to an increasingly influential Russia, China and Iran.

“Occupying a pivotal position at the juncture of Europe, Africa, and Asia, the “Greater Middle East” - here defined as the sum of the core Middle East, North Africa, the African Horn, South Asia, and ex-Soviet Central Asia - ikewise occupies a crucial position with respect to some of the major issue areas of the contemporary era”[33]. The offshore balancing is anchored in the National Security Strategy (NSS) of December 2017. As mentioned in the NSS, “the United States will respond to the growing political, economic, and military competitions we face around the world. China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity”[34]. Concerning the instance of the Middle East in light of the 21st century, the US strategy is also to contain the rise of Iran as a regional power. Since 1983, CENTCOM has maintained responsibility of the Middle East, which is located on the borders of the Rimland[35]. This region is exploited for its lucrative energy deposits and politically dominated by foreign powers.

The control of the Middle East provides an opportunity for the American Navy to contain (diplomatically and militarily) an emergence of Chinese, Russian, and Iranian power[36]. In fact, during the last decade, the geopolitical configurations were reshaped by the presence of those three powers in the Middle East, challenging the American posture. Russia has emerged as a key power broker and military actor in the region by acquiring two strategic locations (the naval facility located in Tartus and an air force base in Latakia). The acquisition of the naval facility in Tartus is a step forward to allow Russia achieve their geopolitical ambition: to have access to warm waters. Despite being a “land fortress” (Mackinder), Moscow is investing more and more in naval equipment to access warm waters. “By controlling Syria’s littoral waters, Russia is inserting itself in a region that is either strongly allied to the United States (Israel and Saudi Arabia) or highly opposed to it (Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon)”[37]. Additionally, China is attempting to emerge as a player in the Middle East region as well. In fact, for the first time, the Middle Empire published in January 2016 an Arab Policy Paper[38] to deepen China-Arab strategic cooperative relations. This cooperation is part of the renewal of the Silk Road project. In a geopolitical approach, the OBOR[39] project tends to unify Spykman’s Rimland while opening-up Mackinder’s Heartland[40], owing that to, the increase of connectivity. The OBOR project is a long-term vision for the Middle East. In addition to that, China’s military modernization effort, including its naval section, has become the top focus of US defense planning and budgeting. This can in fact be a threat to the American foreign policy on the Eurasian chessboard. To reflect like Mahan, Russia as well as Pekin are developing their onshore access by acquiring two strategic military bases and implanting the string of pearls ‘strategy (respectively). Beijing is reinventing string of pearls as Maritime Silk Road.

The US should therefore commit to neo-containment as a specific and calibrated response to the emergence and rise of those three powers in the Middle East. Coastal access via American military naval bases, allows American thalassocracy to be present on the Eurasian perimeter. As we approach 30 years following the fall of the Soviet Union, American thalassocracy has the same ambition as it did during the Cold war. In fact, during this period, the adopted American strategy focused on containment in order to prevent the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon. Nowadays, this desire renews itself in a way to prevent the rise of a power state that threatens the American interests in the “World Island” as it was defined by Mackinder[41]. This neo-containment is revealed through the Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative in addition to President Donald Trump’s support to the Three Seas Initiative in Eastern Europe[42]. This can be considered as the restructured version of the containment. The latter is primarily conducted against the Russian and the Chinese and secondly anti-Iranian. In this case, we can absolutely apply Spykman’s famous quote: “Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia; who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the World”.

Conclusion

By lowering America’s politico-military profile in the region, an offshore balancing strategy is advantageous for the US. It contributes de facto to decrease the terrorist threat to the US. “In the Middle East, the pursuit of geopolitical and ideological dominance over there has increased the terrorist threat over here. As Americans come to realize that the strategy of primacy makes the US less secure, they are becoming more receptive to the arguments for an offshore balancing strategy”[43].

The offshore balancing strategy allows the US to contain the increase of Chinese, Russian and Iranian influence in the Middle East. However, this strategy cannot be effective without reconsidering the US naval and maritime forces. As demonstrated, this strategy should be associated with onshore access whether by the physical presence of military bases or by other means such as maintaining a persistent presence through the use of cyber and other related technologies. “Offshore balancing is a grand strategy born of the confidence in the United States’ core traditions and a recognition of its enduring advantages”[44]. The offshore balancing and onshore access strategies are applied on the Eurasian chessboard as stated by Brzezinski. The main objective is to prevent the emergence of a dominant power in Europe and East Asia – a Eurasian hegemon that could cause an existential threat to the US. It is a way to stop the unification of Spykman’s Rimland while opening-up Mackinder’s Heartland.

APPENDIX 1

Source: BRZEZINSKI Zbigniew, The Grand Chessboard. American primacy and its geostrategic imperatives, Basic Books, 1998, p.15.

APPENDIX 2

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

- Mahan, Thayer Alfred, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1660-1783), Little, Brown and Co, 1890.

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew, The Grand Chessboard. American primacy and its geostrategic imperatives, Basic Books, 1998.

- Lutz, Catherine, The bases of Empire. The Global Struggle against US Military Posts, New York University Press, 2009.

Journal articles

- Chauhan, Tanvi, “Why are warm-water ports important to Russian Security?” European, Middle Eastern & African Affairs, volume 2, issue 1, 2020, p.57-76.

- Crawford, W Timothy, “Preventing Enemy Coalitions: How Wedge Strategies Shape Power Politics”, International Security, volume 35, issue 4, 2011, p.155-189.

- Harkavy, Robert, “Strategic Geography and the Greater Middle East”, Naval War College Review, volume 5, number 4, article 4, 2001.

- Hooker Jr, R.D, “The Grand Strategy of the United States”, INSS Strategic Monograph, National Defense University Press, Washington DC, 2014.

- Layne, Christopher, “Preponderance to offshore balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy”, International Security, volume 22, issue 1, 1997, p.86-124.

- Layne, Christopher, “America’s Middle East grand strategy after Iraq: the moment for offshore balancing has arrived”, Review of International Studies, volume 35, issue 1, 2009, p.5-25.

- Lewis, W. John & Litai Xue., “China’s security agenda transcends the South China Sea”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, volume 72, number 4, 2016, p.212-221.

- Zakaria, Fareed, “The future of American power: how America can survive the rise of the rest”, Foreign Affairs, volume 87, issue 3, 2008 p.18-43.

Reports

- Department of Defense, Sustaining US Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, 2012. https://archive.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf

- The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, 2017. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf

- The Chinese Government, China Arab Policy Paper, 2016.

http://www.china.org.cn/world/2016-01/14/content_37573547.htm

Articles

- Buyon, Noah and Gramer, Robbie, “Trump stumbles into Europe’s pipeline politics”, Foreign Policy, 2017. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/07/06/trump-stumbles-into-europes-pipeline-politics-putin-europe-poland-liquified-natural-gas-three-seas-initiative/

- Kaplan, Robert, “America’s Elegant Decline”, The Atlantic, 2007. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/11/america-s-elegant-decline/306344/

- Layne, Christopher, “The fact of US decline is undeniable. A new grand strategy is in order”, National Interest. 2012. https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/almost-triumph-offshore-balancing-6405

- Maurer, John, “The influence of thinkers and ideas on History: the case of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2016. https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/08/influence-thinkers-ideas-history-case-alfred-thayer-mahan/

- Mearsheimer, J.John and Walt, M.Stephen, “The case for offshore balancing, a superior US Grand Strategy”, Foreign Affairs, 2016. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing

- Sempa, P. Francis, “The Geopolitical Vision of Alfred Thayer Mahan”, The Diplomat, 2014. https://thediplomat.com/2014/12/the-geopolitical-vision-of-alfred-thayer-mahan/

- Walt, M Stephen, “The United States Forgot its Strategy for Winning Cold Wars”, Foreign Policy, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/05/offshore-balancing-cold-war-china-us-grand-strategy/

Thesis, articles and books in foreign language

- Fleury, Christophe, Discontuinuités et systèmes spatiaux. La combinaison île/frontière à travers les exemples de Jersey, de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon et de Trinidad. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université de Caen, 2006.

- Samaan, Jean-Loup, «L’offshore balancing américain dans le golfe Persique, Vertus et limites d’une stratégie», Enjeux géostratégiques au Moyen-Orient, volume 47, issue 2-3, Septembre 2016 p.178-186. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ei/2016-v47-n2-3-ei03031/1039542ar/

- Zajec, Olivier, «Offshore Balancing and Onshore Access: la place de l’accès au littoral dans la culture thalassocratique américaine». Note de recherche de l’IESD, Coll. Pensée stratégique, number 2, December 2019.

- Zajec, Olivier, Introduction à l’analyse géopolitique: Histoire, Outils, Méthodes, Editions du Rocher, 2018.

[1]- Translated from French: «insularité cela veut dire isolement, refuge, repli, mépris de l’étranger et dispositions conservatrices. Mais cela veut aussi dire appel au large, innovation au voyage, simulation des puissances d’expansion». Maxe Sorre cite in Christophe. Fleury, Discontuinuités et systèmes spatiaux. La combinaison île/frontière à travers les exemples de Jersey, de Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon et de Trinidad, Sciences de l’Homme et Société, Université de Caen, 2006.

[2]- Olivier, Zajec, «Offshore Balancing and Onshore Access: la place de l’accès au littoral dans la culture thalassocratique américaine», Note de recherche de l’IESD, Coll. Pensée stratégique, number 2, december 2019, p.5.

[3]- Fareed, Zakaria, “The future of American Power”, Foreign Affairs, volume 87, issue 3, 2008, pp.18-43, p.19.

[4]- John H, Maurer, “The influence of thinkers and ideas on History: the case of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2016 https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/08/influence-thinkers-ideas-history-case-alfred-thayer-mahan/

[5]- He famously listed six fundamental elements of sea power: geographical position, physical conformation, extent of territory, size of population, character of the people and character of government. For more information, refer to Francis P, Sempa, “The Geopolitical Vision of Alfred Thayer Mahan”, The Diplomat, 2014. https://thediplomat.com/2014/12/the-geopolitical-vision-of-alfred-thayer-mahan/

[6]- John H, Maurer, op.cit.

[7]- John H, Maurer, ibid.

[8]- John J, Mearsheimer, and Stephen M, Walt, “The case for offshore balancing, a superior US Grand Strategy”, Foreign Affairs, 2016. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing

[9]- John W, Lewis, & Xue, Litai, “China’s security agenda transcends the South China Sea”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, volume 72, number 4, 2016, pp.212-221, p.217.

[10]- Robert, Kaplan, “America’s Elegant Decline”, The Atlantic, 2007. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/11/america-s-elegant-decline/306344/

[11]- Catherine, Lutz, The bases of Empire. The Global Struggle against US Military Posts, New York University Press, 2009, pp.7.

[12]- Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1660-1783), Little, Brown and Co, 1890, pp.84.

[13]- Catherine, Lutz, op.cit, pp.6.

[14]- Catherine, Lutz, ibid, pp.7.

[15]- Fareed, Zakaria, op.cit, p.42.

[16]- Fareed, Zakaria, ibid, p.42.

[17]- R.D, Hooker Jr, “The Grand Strategy of the United States”, INSS Strategic Monograph, National Defense University Press, Washington DC, 2014, p.1.

[18]- John J, Mearsheimer, and Stephen M, Walt, op.cit.

[19]- Stephen M, Walt, “The United States Forgot its Strategy for Winning Cold Wars”, Foreign Policy, 2020.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/05/offshore-balancing-cold-war-china-us-grand-strategy/

[20]- Christopher, Layne, “America’s Middle East grand strategy after Iraq: the moment for offshore balancing has arrived”, Review of International Studies, volume 35, issue 1, 2009, pp.5-25, p.10.

[21]- Timothy W, Crawford, W Timothy, “Preventing Enemy Coalitions: How Wedge Strategies Shape Power Politics”, International Security, volume 35, issue 4, 2011, pp.155-189, p.158.

[22]- Christopher, Layne, op.cit, p.12-13.

[23]- Jean-Loup, Samaan, «L’offshore balancing américain dans le golfe Persique, Vertus et limites d’une stratégie», Enjeux géostratégiques au Moyen-Orient, volume 47, issue 2-3, Septembre 2016 pp.178-186, p.178.

[24]- Christopher, Layne, “Preponderance to offshore balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy”, International Security, volume 22, issue 1, 1997, pp.86-124, p.87.

[25]- Christopher, Layne, “The fact of US decline is undeniable. A new grand strategy is in order”, National Interest, 2012. https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/almost-triumph-offshore-balancing-6405

[26]- Christopher, Layne, op.cit.

[27]- Department of Defense, Sustaining US Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, 2012, p.3. https://archive.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf

[28]- See appendix 1.

[29]- The Rimland is divided into three sections: the European coast land, the Arabian-Middle East desert land and the Asiatic monsoon land. The Rimland also refers to Mackinder’s Inner or Marginal Crescent. Spykman emphasizes on the notion of Rimland at the expense of Mackinder’s Heartland.

[30]- For Mackinder, the “World Island” is Eurasia. Its center is called the Heartland which is confused with Russia.

[31]- Zbigniew, Brzezinzki, The Grand Chessboard. American primacy and its geostrategic imperatives, Basic Books 1998, pp.15.

[32]- Zbigniew, Brzezinzki, op.cit, pp.17.

[33]- Robert, Harkavy, “Strategic Geography and the Greater Middle East”, Naval War College Review, volume 5, number 4, article 4, 2001, p.2.

[34]- The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, 2017, p.2. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf

[35]- The US created seven regional geographic combat commands: Africa Command (USAFRICOM), Central Command (USCENTCOM), European Command (USEUCOM), Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM), Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) and Space Command (USSPACECOM).

[36]- Olivier, Zajec, Introduction à l’analyse géopolitique: Histoire, Outils, Méthodes, Editions du Rocher, 2018, pp.57.

[37]- Tanvi, Chauhan, “Why are warm-water ports important to Russian Security?” European, Middle Eastern & African Affairs, volume 2, issue 1, 2020, p.66.

[38]- The Chinese Government, China Arab Policy Paper, 2016.

http://www.china.org.cn/world/2016-01/14/content_37573547.htm

[39]- See appendix 2.

[40]- Olivier, Zajec, op.cit, pp.224.

[41]- Olivier, Zajec, op.cit, p.15.

[42]- Noah, Buyon and Robbie, Gramer, “Trump stumbles into Europe’s pipeline politics”, Foreign Policy, 2017. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/07/06/trump-stumbles-into-europes-pipeline-politics-putin-europe-poland-liquified-natural-gas-three-seas-initiative/

[43]- Christopher, Layne, ibid, p.24.

[44]- John J, Mearsheimer, and Stephen M, Walt, ibid.

الموازنة الخارجية في الثقافة الأميركية: استراتيجية بديلة للشرق الأوسط

تميز العقد 2000 بالتدخلات العسكرية الأميركية في العراق وأفغانستان لإنشاء الديموقراطية، ما جعلت هذه التدخلات من إدارة أوباما تبحث - على الأقل نظريًا - عن التوازن بين الحفاظ على قيادة الولايات المتحدة في العلاقات الدولية وجدوى الانسحاب من الصراعات الإقليمية، وكان عليها أن تعيد النظر لاستراتيجية الولايات المتحدة في أعقاب الفوضى التي خلقتها إدارة بوش في الشرق الأوسط.

إن استراتيجية الموازنة الخارجية هي مفهوم برنامج ظهر في التسعينيات في مراكز البحوث الأميركية بعد انهيار الاتحاد السوفياتي، وهي نابعة من التقاليد الأساسية للولايات المتحدة والوعي لمزاياها الاستراتيجية. لذلك، فإن الولايات المتحدة تستغل موقعها الجغرافي وتسعى إلى التصدي لطموحات القوة القادمة من جيرانها. هذه الاستراتيجية هي رمز لمبادىء الأدميرال ألفريد ثاير ماهان الاستراتيجية.

تسعى الولايات المتحدة إلى منع ظهور القوة المهيمنة في أوروبا وشرق آسيا، مع ظهور قوى إقليمية ودولية تحديدًا في الشرق الأوسط، فيمكن أن تسبب هيمنة أوراسيا تهديدًا وجوديًا للوضع الأميركي.