- En

- Fr

- عربي

Revisiting Geopolitics in the Wake of the Russian-Chinese Alignment

Introduction

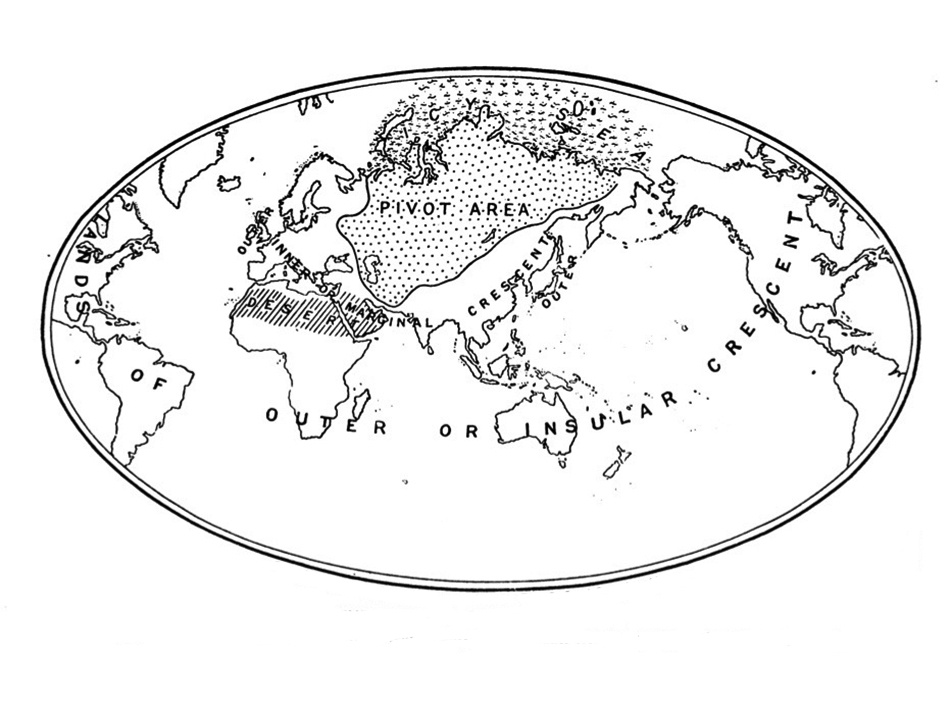

The world today hardly resembles the one that Halford Mackinder examined in 1904 when he first analyzed the advantages of controlling the Eurasian continent. Today, the interest in the pivot area1 Mackinder saw as the basis for achieving world dominance is emerging. His 1919 updated vision of the pivot area which he referred to as the “Heartland” of Eurasia has a crucial role in the policy of today's superpower toward that region, which has a huge influence upon the entire international system2.

The recent global developments show geopolitical considerations driving economy and trade and reflecting geographic, cultural, and strategic direction. Lessons from emerging geopolitics include the ongoing competition between the United States of America and China, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and all related proxy wars and military interventions in the course of exercising influence all over the globe, from Asia to Africa and even to Europe, where illegal immigration and refugee flows are threatening the old continent’s stability for the first time since the end of the cold war.

Geography shaped international relations for years and is still doing this. Geographic location shapes the factors that drive any state action.4 When Harlford Mackinder expressed his fears of any alignment between Russia and Germany in the 20th century5, he was also driven by geography. For sure geographic location is not the only factor that affects the State’s policies, as many others are involved also, such as economy, culture, religion, natural resources, as well external opportunities6.

In 1904, Mackinder wrote that “The oversetting of the balance of power in favor of the pivot state, resulting in its expansion over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia, would permit the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would then be in sight”7. This might happen, he added, if Germany allied with Russia8.

On the other hand, Mackinder did not disregard China. In his 1904 article, he saw China as a potential candidate for control of the core of Euro-Asia, who would overthrow the Russian empire and conquer its territory9. Further, and more precisely, Mackinder states that China might “constitute the yellow peril to the world’s freedom just because they would add an oceanic frontage to the resources of the great continent”10.

With the current alignment between China and Russia, things seem to be heading towards countless complications. With the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)11, China can act as a strategic depth for Russia and vice versa. Any American strategy to confront China without considering Russia will fail. As this been said, any Strategy with this aim must mirror Kissinger’s “triangular diplomacy” model, which played an important role in preventing the alliance between China and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

This paper focuses on the relevance of Mackinder’s geopolitical assessments in the current geopolitical context, where the Russian and Chinese alignment is threatening Western policies, especially the United States’ global dominance, and the consequences of any strategies aiming to disconnect China from Russia.

Geopolitical perceptions

Geopolitics is traditionally defined as the study of "the influence of geographical factors on political action"12. Henry Kissinger used this term to define how to preserve equilibrium in global politics13. Geopolitics has become synonymous with grand strategy in the everyday tactical conduct of statecraft14, particularly when the geopolitical perceptive offers the framings within which grand strategy is assembled15.

Geopolitical Theories are usually shaped by the geopolitical environment that emerges due to global competition, technological advancements, and shifting power dynamics16. They emerge as a response to strategic needs and have a lasting influence on geopolitical thought, particularly in understanding the strategic significance of geography in global power dynamics. Areas of geopolitics deal with relations between the interests of international political players focused within a geographical element creating a special geopolitical system17.

When Halford Mackinder's “Geographical Pivot of History” was first articulated in 1904, the international situation was shaped then by the political environment of the early 20th century. Many key factors influenced its development, mainly what was related to the evolution of nationalism and autocracy. As such, many states were looking for greater dominance, where their spheres of influence intersected, and what was intended to be a peaceful post-war era, changed to be an era of geopolitical competition which reached its culmination point in 1939 when the Second World War broke out.

The Colonial Rivalries were driven by competition among them, particularly Britain, France, Germany, and Russia. The scramble for colonies in Africa, Asia, and other regions heightened the strategic importance of territorial control. As such, the British Geopolitical Concerns were focused on maintaining the country’s supremacy.

In 1919, Mackinder's “Heartland Theory” emerged in the context of existing geopolitical and geographic-based theories, such as the Seapower theory emphasized by Alfred Thayer Mahan and the organic state theory underlined by Friedrich Ratzel18. Mackinder's work was part of a broader intellectual movement that sought to understand the influence of geography on political power19. He was concerned with preserving British dominance and was looking into how to counterbalance other emerging powers, trying to control strategic land areas that are vital to maintain strong military power, in an era where technological advances were making the impossible easy.

Mackinder’s main focus was central Eurasia, the Heartland, where railroads and improvements in land transportation shifted the strategic calculus20 . Previously, sea power had been the dominant factor in global dominance, but the ability to move troops and resources quickly across vast landmasses made control of central Eurasia increasingly significant21.

Mackinder’s theory suggested that the control of Eurasia's central landmass was crucial for global dominance. This was driven by the impacts of the First World War and the subsequent redrawing of national boundaries which reshaped the geopolitical considerations22.

The emergence of the United States of America and Japan as significant global naval powers began to shift the balance of power away from Europe. Mackinder's theory took into account the need to counterbalance these rising powers, and at the same time, he looked at the Russian territorial ambitions and its potential to control the vast Eurasian landmass as a central concern. The Russian Empire's expansion and growing influence in Central Asia and Siberia posed a direct challenge to British interests in India and beyond.

Mackinder identified the central area of Eurasia as the “Pivot Area” which he believed was the key to controlling the world23. After he updated his theory in 1919, Mackinder famously stated, “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; who rules the World Island commands the world.”24 The World Island he identified includes the interlinked continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe25. This was the largest, most populous, and richest of all possible land combinations. His main argument was that The Heartland is protected by natural barriers, such as deserts and mountains26, making it difficult for naval powers to penetrate, in addition to its vast natural resources, which would be crucial for sustaining a powerful empire.

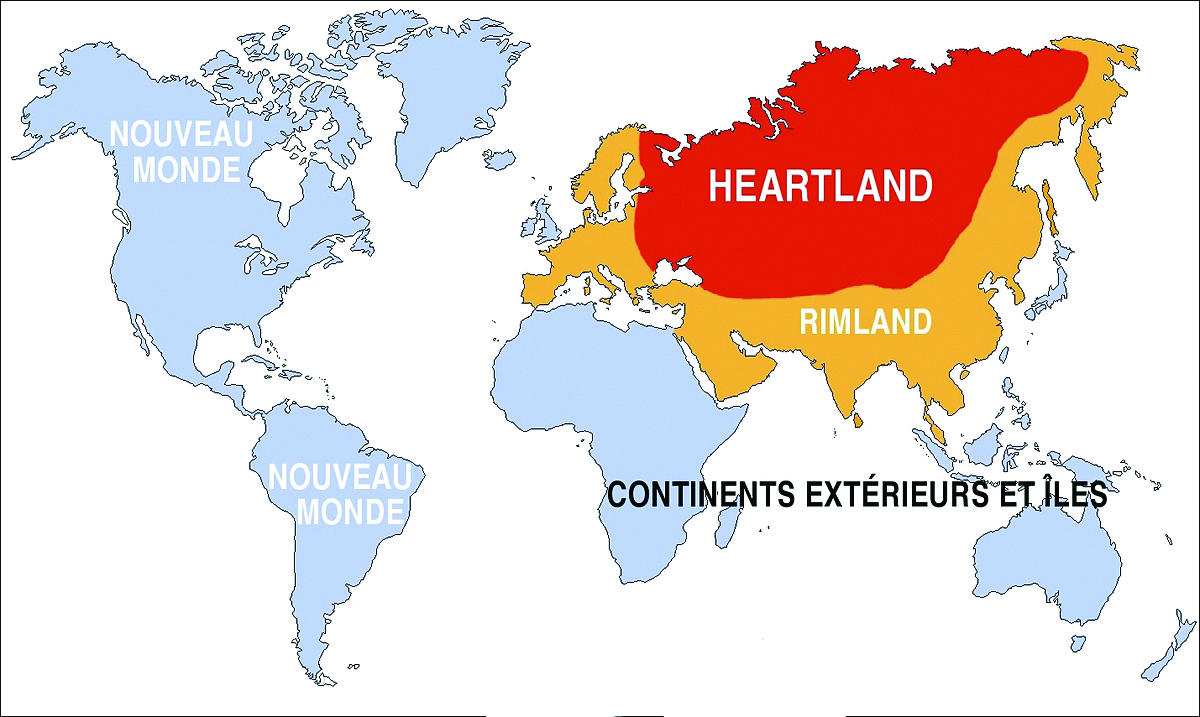

Mackinder's ideas were initially met with skepticism. Although many strategists and policymakers were still focused on the importance of sea power, the Heartland theory influenced some of them, such as Nicholas Spykman, whose Rimland theory was built upon and modified Mackinder’s ideas.

Nicholas Spykman's Rimland theory, developed as a counterpoint to Mackinder's ideas, argues that the coastal fringes of Eurasia, which he called the Rimland, are more crucial to controlling the global balance of power, as he saw that the heartland is not important if it cannot be defended on the Rimland and if its resources cannot be transported through them. He believed that the Rimland, which includes Western Europe, the Middle East, and Asia's coastal areas, holds the key to global domination. He famously stated, “Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia; who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.”27 By this new approach, Spykman placed an American sight on geopolitical theory and placed the rational basis for George Kennan's28 first thoughts to establish a strong federation in Western Europe to counter the Soviet influence in Europe29, and then his views on the containment explained in “The Long Telegram” he sent to Washington30, in which he explained the Soviet behavior and the needed response to counter it, in which he argued that the West must take steps to strengthen the “Rimland” to contain the Soviet Union, in case the later use its control of the “Heartland” to command the World Island31.

Inasmuch, when Mackinder's views on the benefits of controlling the Eurasian landmass became integrated with the Cold War American strategic thought and policy, it was believed that his views affected US foreign policy throughout the Cold War era. In this context, Colin Gray wrote:

… the overarching vision of US national security was explicitly geopolitical and directly traceable to the heartland theory of Mackinder … Mackinder's relevance to the containment of a heartland-occupying Soviet Union in the Cold War was so apparent as to approach the status of a cliché32.

What has changed? How did the post-Cold era affect the strategic approach to US national security? Is the Mackinder “Heartland” still the guiding principle to the US strategic thought and policy? Today, the main concern for the US is seen to be China. Senator J.D. Vance as a vice presidential running mate for Donald Trump provides more evidence of what would be a tough US stance on China in a second Trump administration, as he called China the “biggest threat”33. So, in the same context of Gray’s views over the importance of the “Heartland” in driving the US Cold War policy, China, which covers a crucial part of Spykman’s “Rimland”, and digressively a part of Mackinder’s “Inner Marginal Crescent”34, reinforced by its emerging alliance with Russia, will be a key future actor that will play the same role as the “heartland” did before.

Current Geopolitical Context

The re-emergence of Russia as a regional power, aiming at playing a considerable role internationally is seen as a real concern by the West. Russia, occupying a significant portion of Mackinder's Heartland, remains a central power in Eurasia. Its vast landmass, natural resources, and strategic position make it a key player in Eurasian geopolitics. The Russian efforts to maintain influence in Central Asia and Eastern Europe align with Mackinder's view that controlling this region is crucial to preserve power. The war in Ukraine and the Russian Central Asian policies demonstrate the Russian goals worldwide. In its course to protect the Eurasian ambitions, Russia looked for China as the most relevant “rival” in confronting the West regionally and internationally.

China, situated on the eastern edge of Spykman’s Rimland, has been expanding its influence through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beijing’s political and international ambitions made the Chinese expand their cooperation with their competing neighbor, Russia, in an attempt to build larger universal control and oppose US superiority.

In this concept, the Chinese maritime strategy, including its activities in the South China Sea and its naval expansion, aligns with Spykman's emphasis on controlling the Rimland. As a Rimland power aligned with a Heartland power, China and Russia's alignment can be seen as a merger of Mackinder-Spykman geopolitical insights, creating a formidable Eurasian axis, that offers dominant strategic cooperation in all dimensions of international power, which is very hard to overcome.

Moreover, and as we mentioned before, when Mackinder expressed his concerns about any expansion that merges the mass lands of Asia and Europe, he saw an alignment between Germany and Russia as a good example of such expansion. In the same context, he wondered if “the great continent, the whole world Island or a large part of it, were at some future time to become a single and united base of sea power”35. In the perspective of Mackinder’s notice, the current alignment between China and Russia paves the way for such a united base, with a part of the Rimland, in this case, China, acting as a buffer region located between the heartland and the marginal seas, linking the Eurasian landmass, in this case Russia, with the shores of the South China Sea, allowing the Russian Navy, in combination with the Chinese, to project their sea power, starting from this sensitive region to the whole world.

On the other hand, the fear that such a Eurasian alliance would be able to disrupt trade with the United States, ruining its economy and standard of living is factual. The BRI connects the economic powerhouses of East Asia with the resources of Central Asia and beyond, linking Mackinder's Heartland with Spykman's Rimland. This economic initiative is reinforced by military integration between the two countries36. Joint military drills and defense cooperation between Russia and China enhance their strategic positions in both the Heartland and the Rimland, and their aim to counterbalance the West, elevating their partnership consequently37, and coordinating “within and across international institutions to challenge the norms of the U.S.-led world order”38.

Moscow and Beijing view their orientation as an equalizer to Western influence, particularly that of the United States and NATO. This alignment seeks to challenge Western dominance in global affairs39, and to create a stabilizing effect in the two state’s respective regions, allowing both nations to project power more effectively and resist external pressures40. This stability in the Heartland and Rimland makes it harder for external powers to disrupt their strategic interests.

Understanding this alignment through its geopolitical frameworks highlights the need for a comprehensive strategy that addresses both the Heartland and Rimland and works through three tracks simultaneously, in Eurasia, the sea, and the economy. Mackinder had already expressed his insights on a united world Island, where the railways and aero plane routes will make the deployment of military forces easier, and thus more effective. He looked at this unity as an advantage for land forces over sea forces, where not only the Trans-Continental Railway but also the motor-cars and aero planes can play a crucial role in the favor of the Land powers, where Modem artillery in this concept, is very formidable against ships41.

So in order for the West, especially the US, to be able to stand for the strategic consequences of such alignment, which represents an important portion of the united world island that Mackinder mentioned, Washington and its allies should strengthen their presence and influence in Central Asia and Eastern Europe to counterbalance Russian dominance in the Heartland, and at the same time adopt special strategies to reinforce their alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific region to counter China's influence in the Rimland, a thing that the US already took in its consideration. Moreover, all this must be accompanied with Economic Initiatives (EI) to Promote alternative economic advantages that offer viable options to the BRI that can help limit China's expanding influence. On the other hand, a new “triangular diplomacy” approach is crucial for any effective strategy that will challenge this alignment.

A new “triangular diplomacy” approach

The “triangular diplomacy” concept, created by Henry Kissinger 43, was a strategic framework used during the Nixon administration to navigate the complex dynamics of the Cold War, particularly the relationships between the United States, the Soviet Union, and China44. President Richard Nixon’s great achievement was organizing a diplomatic approach to Beijing two years after China’s seven months border clashes with the Soviet Union45. This policy helped the West to accomplish victory in the Cold War, not militarily, but geopolitically46.

The triangular diplomacy concept included three main elements that were the basis which Nixon’s administration worked on, the first was stressing on the Detente with the Soviet Union, the second was the opening of relations with China and the last was maintaining strong alliances with allies.

In its core intentions, the “triangular diplomacy” aimed then at easing tensions and promoting peaceful coexistence with the Soviet Union. It involved negotiations on arms control, and efforts to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict. Improvement in American relations with the Soviet Union was crowned by an invitation for President Nixon to meet with Soviet president Leonid Brezhnev, allowing Nixon to become the first American President to visit Moscow. This visit was very successful regarding the treaties signed to control nuclear arms, paving the way for future treaties which aimed to reduce and eliminate arms47.

On the other hand, this policy involved improving relations with the People's Republic of China, which had been largely isolated from the West since the Communist revolution in 1949. This development lead to the eventual normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries, and allowing the UN General Assembly to pass the United Nations Resolution 2758 (XXVI) which replaced the Republic of China (ROC) by the People Republic of China (PRC) as a permanent member of the Security Council in the United Nations in 197148. The groundbreaking visit of President Nixon to China in 1972 was a key moment in this policy, which aimed to easing Cold War tensions, and to use the strengthened relations with Moscow and Beijing as leverage to pressure North Vietnam to end the war49. At the same time, this policy focused on maintaining and strengthening alliances with traditional allies in Europe and Asia to ensure a balanced approach in dealing with both the Soviet Union and the people’s republic of China.

What helped achieving this policy goals was the significance of the surrounding environment then. By the late 1960s, the relationship between China and the Soviet Union had significantly deteriorated due to ideological, territorial, and strategic disputes, which led to the border military clashes between them. Kissinger and Nixon saw an opportunity to exploit the rift, encouraging China to view the Soviet Union as a threat.50 By reaching out to China and improving US-China relations, Beijing was provided with a strategic counterbalance to the Soviet Union. China saw the rapprochement with the United States as a way to gain leverage against Soviet pressure and reduce its strategic vulnerability. This realignment weakened the possibility of a united communist front against the United States and its allies51.

On the other hand, by engaging both the Soviet Union and China diplomatically, the United States gained strategic leverage also. The improved US-China relationship created a perfect opportunity for the US to play the two communist giants against each other, making it difficult for them to align their policies against American interests52, creating a more balanced global power structure. A good question to be asked, is whether mirroring this policy nowadays will lead to the same results achieved during the cold war era.

Currently, the success in implementing a new "triangular diplomacy" to split Russia under Putin from China is questionable, given the contemporary geopolitical landscape. Such a policy would need to consider the current strategic, economic, and ideological dynamics between the two countries, as well as the broader international context.

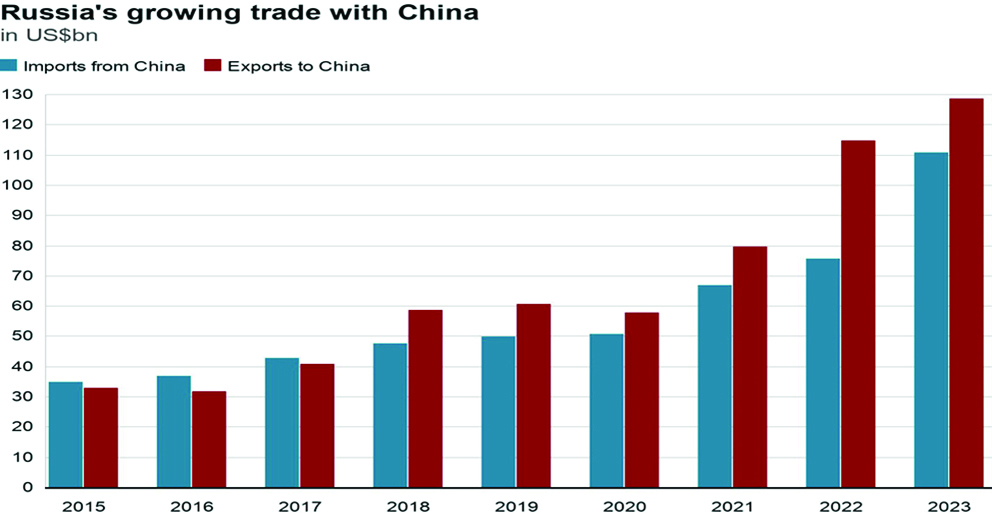

Any outlook in the perspective of a new “triangular diplomacy” needs long term strategies. Aspects that might inform a new version of a “triangular diplomacy”, must take in consideration the new international environment, and address the security concerns of Russia and china as well, and the unpredicted consequences of the ongoing war in Ukraine, as well as the disputes in the South China sea and the Taiwan issue. While the war in Ukraine is a significant component of Russia's current foreign policy and strategic calculations, terminating the conflict would not necessarily lead to an automatic cessation of the Russo-Chinese alignment. Wherefore, any prospective policy must have economic and diplomatic steps as a starting point. In order for this to be achieved, easing the economic sanctions on Russia is a good beginning. This might make Russia reconsider its commercial relations with China, but with cautious, taking in consideration the lessons learned from what Moscow is experiencing due to the Western sanctions, that made China the primary trade partner for Russia, making relations between the two countries developing constantly stronger53.

A very important aspect of the Russian Chinese relation should be focused on, is that Russia seems to be a “pawn of China’s geopolitical aspirations”54. This is why, a strategy with targeted economic incentives, coupled with addressing the Russian security concerns, might help Russia adopting a more independent economic policy from China, which will pave the way gradually for building trust and leading for more cooperation in the future.

On the other hand, any steps towards Russia must not be seen as a threat by China. Strengthening Relations with China is important in this context. Cooperation with Beijing on global issues will help reduce tensions, and support building a framework of collaboration and trust. This is foreseen through supporting regional stability in Asia by working with allies and partners to ensure a balance of power that does not excessively threaten China's security interests, thereby eliminating the tension in the South East Asian region, and building trust for better cooperation worldwide.

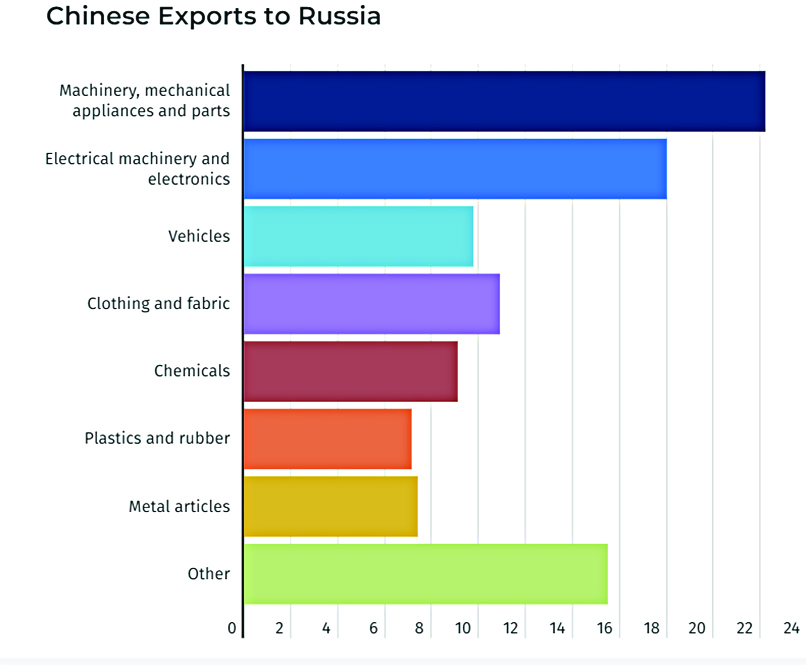

Again, such policies must recognize that changing the strategic calculus of Russia and China is a long-term endeavor that requires sustained effort and consistency, taking in consideration the huge profit China is gaining from this strategic alignment, politically, being labelled as a key player in the emerging world order, and economically, being the superior partner in this relation, where the variance in exports suggests that Russia has become a Chinese petrol station, while China provides almost all necessities for Russia’s struggling war economy, acting as the primary source for Russia’s industrial imports55.

Another aspect a reliable Western Strategy must take in consideration, is that China is still trying to balance its policies to avoid being extremely offensive towards the United States of America and becoming too dependent on Russia57.

Challenges and difficulties

In order to understand the challenges that might encounter such new policy, the facts that steered to the Chinese –Russian alignment must be realized. Today, however, the Western policies and especially the United States is strengthening the two countries relations together58. Basically, the historical grievances and trust deficit are the major drivers that made the two countries look for such orientation. Both Russia and China have historical grievances and a deep-seated mistrust of the West, which lead their rapprochement59.This entente was a result of false economic policies thrusted upon the two countries respectively, which steered an Economic Interdependence between them.

Hence, and due to the present circumstances, efforts to split China and Russia may be perceived as impossible and could potentially backfire, leading to a much stronger alignment against Western interference, as the strategic configuration between the two countries is sustained by many factors and influenced by a complex mix of geopolitical, economic, and strategic elements.

China and Russia today are more firmly aligned than at any time before, with the two countries presidents, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin adopting a vision of reshaping the world order by ending the Western dominance60. This alignment is widely seen within the political support and diplomatic backing between the two states provided in international forums, which was very fruitful in pursuing their international agendas, and providing support to each other's primary ambitions, with Moscow’s support to Beijing over the Taiwan issue and Beijing in return endorsing the Russian efforts to confirm its sovereignty and territorial integrity in reference to the war in Ukraine61. As such, weakening this alignment will be very difficult, if not impossible, given what was achieved until now for both.

As this been said, and in today’s perceptions, the question on the relevance of Mackinder’s geopolitical assessments is important to understand the evolving international relations affecting the changing World Order, especially when related to the global hegemony. Keeping in mind Mackinder’s theory that who rules the heartland commands the World Island, and who rules the World Island will command the World, the Chinese and Russian land masses together widespread larger than Mackinder’s heartland mass, merging an important part of the Rimland features with those of the heartland and concentrating power and resources, a fact that gives the two countries’ alignment a great opportunity to be able to confront the American supremacy, but this still has to be proved.

Moreover, in today’s lenses, it seems that the alignment between China and Russia initiated a strategic merge between Mackinder’s heartland, i.e. Russia, and a very important portion of Spykman’s Rimland, i.e. China. Besides, this merge is already introducing another strategic alignment which covers more Rimland territories, i.e. India and Iran. Looking at this merge through Mackinder’s scope demonstrate again what he described as Britain's fear of the control of the resources of continental Europe by only one power making it in a position to overcome other powers62.

In the same concept, the United States was trying to stop any unity that opposes its ambitions. By revisiting history, and until recently, it appears that Mackinder may originally has placed the key geographical position in the incorrect side of the globe. History did not prove yet that the Eastern Hemisphere grants any strategic advantage over the Western one. In fact, control over the Western Hemisphere gave the United States, until now, and in different occasions, the ability to grow to an exceptional super power, thanks to what was identified by Mackinder as elements of power within the Heartland63.

In the same perspective, and according to Fettweis, an island power such as the United States, bordering Eurasia, can guarantee it’s safety by preventing the continent from unifying against her64. But the unification idea, seen in the alignment between China and Russia is believed to be growing through concrete alliance between the two main components of the continent, in a way that shows a solid progress in challenging the American dominance wide world.

Again, the American punishing approach toward Russia is strengthening an “aggressive and expansionist China by helping it to accumulate greater economic and military power”65. With the war in Ukraine keeping the U.S. busy in Europe, Beijing might see a window of opportunity to achieve the Chinese historic mission to re-unite the historic land of China by using military power for annexing Taiwan. The Chinese president made it clear by declaring that the “essence of his national rejuvenation drive is the unification of the motherland”66.

Arguably, achieving this unification seems to be more imaginable with China having Russia to her side, as the two nuclear powers can mobilize together, in war time, a huge military force that may deter any possible intervention of any other state, even if it is the United States.

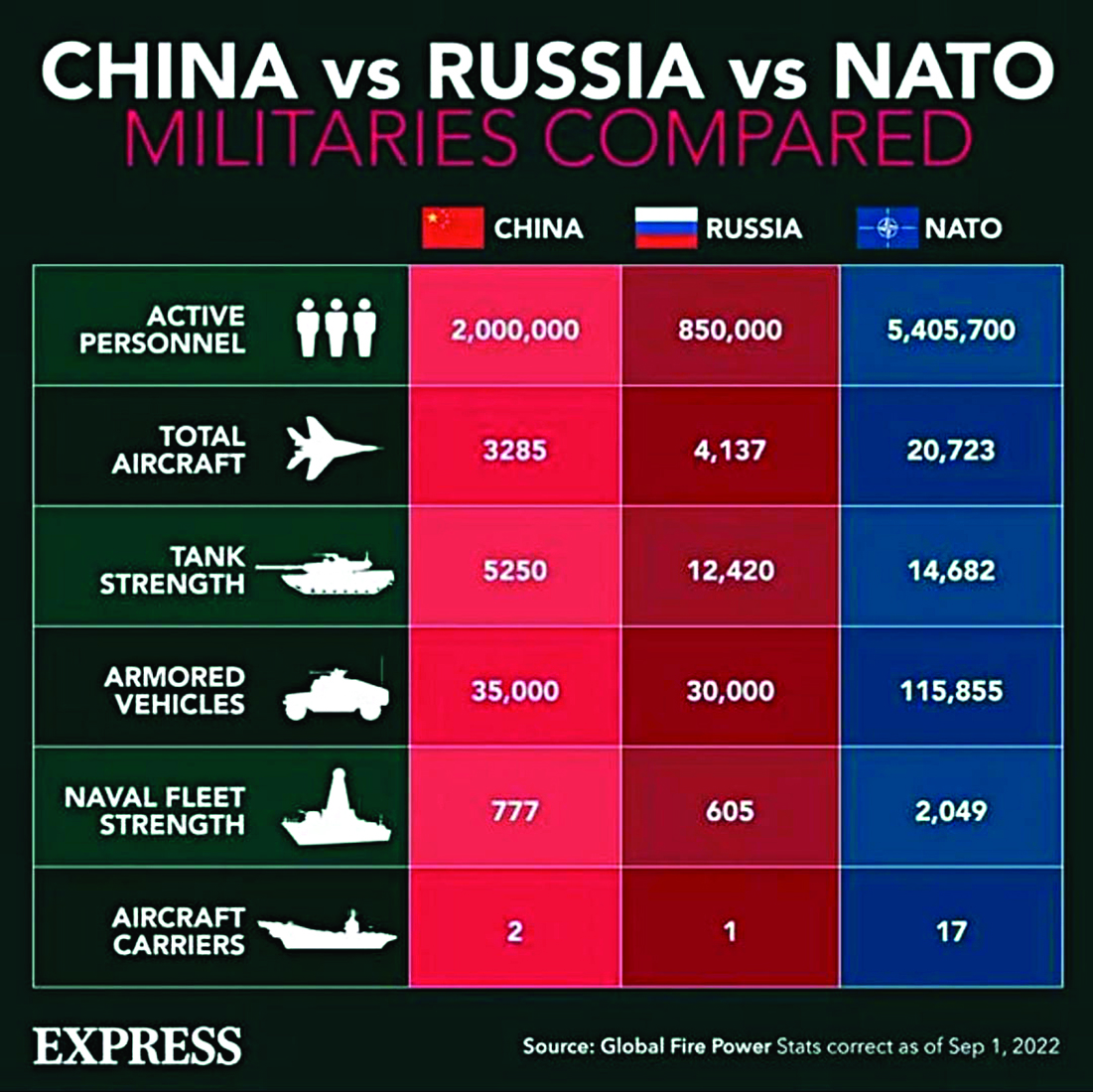

From a military perspective, although the American military power combined with that of NATO other members seems to dominate both China and Russia combined forces, (see the above comparison table), but it is not evident that NATO members will, or have plans to mobilize their military forces against China, for instance, in case of military conflict outbreak in south East Asia, if the American territories were not in under attack68. This is why the United States of America is looking for alternatives with other countries, mainly the United Kingdom, and Australia and inking a defensive agreement (AUKUS) with them that is “intended to strengthen the ability of each government to support security and defense interests, building on longstanding and ongoing bilateral ties”69, where the main sphere of focus of this agreement is generally the South China Sea region. Moreover, and in order to maintain a strong presence to face China’s pearl necklace strategy70, the US inked with the Philippines in 2014 a defensive agreement71 which enables military bilateral training, rapid response for natural crisis and to achieve modernization goals72.

Conversely, in the case of Chinese-Russian military relations, the joint military drills between the two countries could be seen as a clear evidence on their commitment towards helping each other, as there is no legal constrains that don’t allow it, taking in consideration the nature of the decision making process in both countries. Moreover, Moscow’s technological advance in weaponry manufacturing, added to lessons learned and well-tested battlefield tactics in Ukraine, could prove useful to China and might affect its military strategy with regard to the Taiwanese issue. Growing defense cooperation between Moscow and Beijing might lead to cheap Russian weapons and technologies made in China. Such arms sales could increase Russia and China’s influence in conflict-driven regions, damaging the American relationships with its partners73. This military show off demonstrates the deep problems that may face any future attempts to split Russia from China in the present circumstances.

From an economic perspective, and as mentioned before, the economic bonds are getting stronger between the two countries. The graph below shows Russia’s growing trade with China. More importantly, besides that the volume of exports to Russia is significant, China is now the only major industrial nation that still trades with Russia largely without restrictions.74 This adds additional strength to the two countries economic relations, and makes Russia more attracted to it, especially when it comes to the exchange currency, where both countries agreed on conducting trade in Chinese yuan75.

Moreover, an important aspect which must be considered is that China and Russia have also associated themselves within many political and economic organizations aiming to oppose the U.S. influence in the world. Both countries have established and reinforced the growth and the flourishment of these institutions, mainly the BRICS organization, alongside with Brazil, India, and South Africa, which is getting bigger with more countries joining it, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) which is playing a crucial economic role for both countries.

Looking at the beginnings of the BRICS organization when started as BRIC and considering its rapid development since it was established, it has proved itself so far as an effective instrument for global influence since its foundation in 2006, and the joining of South Africa in 2010 making it BRICS77. The main focus of the BRICS today aims to confront the American influence by promoting de-dollarization to challenge the global dominance of the U.S. dollar. The joining of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates in 2024 to BRICS78, added more strength to the future of this organization allowing it to play a dominant role, consolidating the intended approach of China and Russia for reaching their global objective worldwide.

Conclusion

Today’s alignment between Russia and China is adding complexity to the international theatre of influence, and consolidating the opposing force against the American hegemony worldwide. Taking in consideration the geopolitical assessment of such alignment, it’s obvious that today’s environment is very different than the cold war era. As such, it seems very difficult for the United States to overcome such changes without any negative impacts.

While the termination of the war in Ukraine could create opportunities for changes in the Russia-China alignment, it is unlikely to be the sole determining factor. The deep-rooted geopolitical, economic, and strategic ties between the two countries suggest that their partnership will likely continue, albeit potentially with some adjustments.

Significant shifts in this alignment would require a broader reconfiguration of international relations, including changes in Western policies towards Russia and shifts in the internal and external strategic calculations of both Russia and China.

The geopolitical bonds created as a result of the two countries new bilateral and multinational orientation has a significant effect on the nature of the future international relations, which is seen as a reflection of Mackinder’s geopolitical indication that saw China as a potential candidate for control of the core of Euro-Asia, who would overthrow the Russian empire and conquer its territory79, taking in consideration that the present relation between Russia and China is leaning, if it continues on the same track, towards a wide Chinese economic dominance over the Eurasian region as a minimum estimation, threatening the Western policies, especially the United States’ global dominance, mirroring what Mackinder warned about in his geopolitical estimation in 1904.

Finally, joining the Heart Land with China, creates a solid opponent that controls an impressive share of the international power resources, combined with a strong and permanent political will, implies that dealing with the threat imposed from one partner of this alignment and disregarding the other is meaningless, and will not allow a successful outcome. Hence, if the United States of America aims to preserve its global hegemony, a grand strategy aiming to split the Russian Chinese alliance ought to be adopted, as any American approach to tackle what is considered a “Chinese threat” as described by Senator J.D. Vance, must take in consideration the geopolitical effects embedded within this alliance.

Bibliography

Books

1- Charles Kegley and Eugene Wittkopf, World Politics: Trend and Transformation (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005).

2- Harlford Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality (Washington DC: National Defense University press, 1942).

3- Nicholas J. Spykman, The Geography of Peace (New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1944).

Journals

1- Christopher J. Fettweis, “Sir Halford Mackinder, Geopolitics, and Policymaking in the 21st Century”, The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, Vol. 30, No. 2, Summer 2000, pp. 58-71.

2-Colin S. Gray, “The Continued Primacy of Geography,” Orbis, Volume 40, Issue 2, Spring 1996, pp. 247-259.

3- Gearoid Ó Tuathail, “Problematizing Geopolitics: Survey, Statesmanship and Strategy,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 19 (1994).

4- Gearoid Ó Tuathail, “Political Geographers of the Past VIII, Putting Mackinder in his place”, Political Geography, Vol. 11, no. 1, January 1992, pp. 100-118.

5- Harfold Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. xxiii, no. 4, pp.421-437, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1775498

6- Jean Gottman, “The Background of Geopolitics,” Military Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Winter, 1942), pp. 197-206.

7- Miscamble, Wilson D. (May 2004), “George Kennan: A Life in the Foreign service”, Foreign Service Journal, 81 (2), pp. 22–34, ISSN 1094-8120, archived from the original on May 24, 2006, retrieved August 1, 2006.

8- Oliver Krause, “Mackinder’s “heartland” – legitimation of US foreign policy in World War II and the Cold War of the 1950s”, Geographica Helvetica, no. 78, 28 March, 2023, pp.183-197, https://gh.copernicus.org/articles/78/183/2023/

9- Preston Thomas, ““Synergy in Paradox”: Nixon’s Policies toward China and the Soviet Union”, Chicago Journal of History, fall 15, https://cjh.uchicago.edu/issues/fall15/5.3.pdf

10- Vladimir Toncea, 2006, “Geopolitical evolution of borders in Danube Basin,” from Ranjan Sharma, “GEOGRAPHY OF POWER AND INFLUENCE,” International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 13 Issue 01, January 2023, pp.331-341, https://www.ijmra.us/ project%20doc/2023/IJRSS_JANUARY2023/IJRSS37Jan23-RS.pdf

Internet Articles

1- “AUKUS: The Trilateral Security Partnership Between Australia, U.K. and U.S.”, U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Spotlights/AUKUS/

2- “Brics: What is the group and which countries have joined?”, BBC, 1 February 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-66525474

3- “Collective defence and Article 5”, 04 July, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/ en/natohq/topics_110496.htm

4- Aaron Miller, “The Link Between Geography and U.S. Foreign Policy Has Grown More Complex”, Carnegie endowment, April 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/ 04/the-link-between-geography-and-us-foreign-policy-has-grown-more-complex?lang=en

5-Brahma Chellaney, “Growing China-Russia alignment signifies Biden policy failure”, Nikkie Asia, 31 May 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Growing-China-Russia-alignment-signifies-Biden-policy-failure

6- Callum Fraser, “Russia and China: The True Nature of their Cooperation”, RUSI, 7 June 2024, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russia-and-china-true-nature-their-cooperation

7- Charlie Bradley, “Russia and China vs NATO: Military might compared as NATO dominates its enemies”, Express, 1 September 2022, https://www.express.co.uk/news/ world/1663402/russia-china-nato-military-compared-ukraine-taiwan-spt

8- Clara Fong and Lindsay Maizland, “China and Russia: Exploring Ties Between Two Authoritarian Powers”, Council on Foreign relations, 20 March, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/ backgrounder/china-russia-relationship-xi-putin-taiwan-ukraine

9- George Kennan, “The Long Telegram, George Kennan to George Marshall February 22, 1946”, Harry S. Truman Administration File, Elsey Papers, https://web.archive.org/web/ 20141212060658/http://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/study_collections/coldwar/documents/pdf/6-6.pdf

10- Henry Kissinger, The Noble Prize, 1973, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/ peace/1973/kissinger/biographical/

11- Janis Kluge, “Russia-China Economic Relations”, SWP, 16 December 2023, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/russisch-chinesische-wirtschaftsbeziehungen

12- Kelly Ng and Yi Ma, “How is China supporting Russia after it was sanctioned for Ukraine war?”, BBC, 17 May, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/60571253

13- Ken Hughes, “Richard Nixon: Foreign Affairs”, Miller center, University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/president/nixon/foreign-affairs

14- Lee Kuan Yew, “Global Governance: Geopolitical Competition”, School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, 2024, https://intelligence.weforum.org/topics/ a1Gb0000000LHN2EAO/key-issues/a1Gb0000003cNd3EAE

15- Mark Cozad and others, “Future scenarios for Sino-Russian future military cooperation”, Jun 18, 2024, RAND, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2061-5.html

16- Max Bergmann and others, “Collaboration for a Price: Russian Military-Technical Cooperation with China, Iran, and North Korea”, CSIS, 22 May 2024, https://www.csis.org/ analysis/collaboration-price-russian-military-technical-cooperation-china-iran-and-north-korea

17- Maxim Trudolyubov, “China’s Balancing Act Between the U.S. and Russia”, Wilson Center, 24 May 2024, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/chinas-balancing-act-between-us-and-russia

18- Michael Martina and David Brunnstrom, “Trump’s VP pick Vance points to tough China policy, analysts say”, Reuters, July 17, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trumps-vp-pick-vance-points-tough-china-policy-analysts-say-2024-07-16/

19- Simon Dalby, “Geopolitics, Grand Strategy and the Bush Doctrine”, Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, Singapore, October 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/ isn/27169/WP90.pdf

20- The Enhanced Defensive Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) Fact sheet, U.S. Embassy Manila, 20 March 2023, https://ph.usembassy.gov/enhanced-defense-cooperation-agreement-edca-fact-sheet/

UN Resolution

United Nations Resolution 2758 (XXVI), “Restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations”, UN. General Assembly, 26th sess: 1971, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/192054?v=pdf

Referances

1 Today, the pivot area mostly includes Russia, the former Soviet Republics of Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, with some Parts of Mongolia.

2 Christopher J. Fettweis, “Sir Halford Mackinder, Geopolitics, and Policymaking in the 21st Century”, The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, Vol. 30, No. 2, Summer 2000, pp. 58-71. P 58.

3 Harfold Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. xxiii, no. 4, 421-437, p 435, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1775498

4 Aaron Miller, “The Link Between Geography and U.S. Foreign Policy Has Grown More Complex”, Carnegie endowment, April 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/04/the-link-between-geography-and-us-foreign-policy-has-grown-more-complex?lang=en

5 Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, Op. cit. p 436.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, Op. cit. p 437.

10 Ibid.

11 The Belt and Road Initiative, BRI, is a massive infrastructure project led by China, known also as the new Silk Road, aims to stretch the Chinese economic reach, and digressively the Chinese political influence, around the globe. For more information, visit the BRI official Website at: https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/

12 Jean Gottman, "The Background of Geopolitics," Military Affairs, 6 (Winter 1942), 197.

13 Gearoid Ó Tuathail, "Problematizing Geopolitics: Survey, Statesmanship and Strategy," Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 19 (1994), 267.

14 Tuathail, Op. cit.

15 Simon Dalby, “Geopolitics, Grand Strategy and the Bush Doctrine”, Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies,

Singapore, October 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/27169/WP90.pdf

16 Lee Kuan Yew, “Global Governance: Geopolitical Competition”, School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, 2024, https://intelligence.weforum.org/topics/a1Gb0000000LHN2EAO/key-issues/a1Gb0000003cNd3EAE

17 Vladimir Toncea, 2006, "Geopolitical evolution of borders in Danube Basin," from Ranjan Sharma, “GEOGRAPHY OF POWER AND INFLUENCE,” International Journal of Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 13 Issue 01, January 2023, 331-341, p332, https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2023/IJRSS_JANUARY2023/IJRSS37Jan23-RS.pdf

18 Mackinder called the “heartland” of the continent the whole patch extending from the icy flat shore of Siberia in the north, to the steep coasts of Baluchistan and Persia in the south of Asia, and integrated Brandenburg-Prussia, Austria-Hungary, the Baltic Sea, the navigable Middle and Lower Danube, the Black Sea, Asia Minor, Armenia, Persia, Tibet, and Mongolia into his pivot area. See: Harlford Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality (Washington DC: National Defense University press, 1942), p 55, and Oliver Krause, “Mackinder's “heartland” – legitimation of US foreign policy in World War II and the Cold War of the 1950s”, Geographica Helvetica, no. 78, 28 March, 2023, 183-197, p185, https://gh.copernicus.org/articles/78/183/2023/

19 Gearoid Ó Tuathail, “Political Geographers of the Past VIII, Putting Mackinder in his place”, Political Geography, Vol. 11, no. 1, January 1992, 100-118, p 101.

20 Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, Op. cit. p 55.

21 Ibid.

22 Oliver Krause, “Mackinder's “heartland” – legitimation of US foreign policy in World War II and the Cold War of the 1950s”, Geographica Helvetica, no. 78, 28 March, 2023, 183-197, p185, https://gh.copernicus.org/articles/78/183/2023/

23 Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, Op. cit. p 435.

24 Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality Op. cit. p 106.

25 Ibid, 59.

26 Ibid, 54 - 62.

27 Nicholas J. Spykman, The Geography of Peace (New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1944), p. 43.

28 George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was famous for his support to the policy of containment to control the Soviet expansion in the Cold War.

29 Miscamble, Wilson D. (May 2004), "George Kennan: A Life in the Foreign service", Foreign Service Journal, 81 (2): 22–34, ISSN 1094-8120, archived from the original on May 24, 2006, retrieved August 1, 2006.

30 George Kennan, “The Long Telegram, George Kennan to George Marshall February 22, 1946”, Harry S. Truman Administration File, Elsey Papers, https://web.archive.org/web/20141212060658/http://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/study_collections/coldwar/documents/pdf/6-6.pdf

31 Ibid.

32 Colin S. Gray, "The Continued Primacy of Geography," Orbis, 40 (Spring 1996), 258.

33 Michael Martina and David Brunnstrom, “Trump's VP pick Vance points to tough China policy, analysts say”, Reuters, July 17, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trumps-vp-pick-vance-points-tough-china-policy-analysts-say-2024-07-16/

34 See Map at: Harfold Mackinder, “The Geographical pivot of history”, Op. cit, p 435.

35 Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, Op. cit. p 49.

36 Mark Cozad and others, “Future scenarios for Sino-Russian future military cooperation”, Jun 18, 2024, RAND, p 6, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2061-5.html

37 Ibid, p 14.

38 Clara Fong and Lindsay Maizland, “China and Russia: Exploring Ties Between Two Authoritarian Powers”, Council on Foreign relations, 20 March, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-russia-relationship-xi-putin-taiwan-ukraine

39 Ibid.

40 Fong and Maizland, Op. cit.

41 Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, Op. cit. p 80.

42 Ibid, p 81.

43 An American diplomat and political scientist who served as the United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and national security advisor from 1969 to 1975, in the presidential administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. (See: Henry Kissinger, The Noble Prize, 1973, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1973/kissinger/biographical/)

44 Charles Kegley and Eugene Wittkopf, World Politics: Trend and Transformation (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005), p 503.

45 Brahma Chellaney, “Growing China-Russia alignment signifies Biden policy failure”, Nikkie Asia, 31 May 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Growing-China-Russia-alignment-signifies-Biden-policy-failure

46 Ibid.

47 Ken Hughes, “Richard Nixon: Foreign Affairs”, Miller center, University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/president/nixon/foreign-affairs

48 United Nations Resolution 2758 (XXVI) , “Restoration of the lawful rights of the People's Republic of China in the United Nations”, UN. General Assembly, 26th sess: 1971, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/192054?v=pdf

49 Hughes, “Richard Nixon: Foreign Affairs”, Op. cit.

50 Preston Thomas, ““Synergy in Paradox”: Nixon’s Policies toward China and the Soviet Union”, Chicago Journal of History, fall 15, https://cjh.uchicago.edu/issues/fall15/5.3.pdf, p 28.

51 Ibid, p 28.

52 Ibid.

53 Callum Fraser, “Russia and China: The True Nature of their Cooperation”, RUSI, 7 June 2024, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russia-and-china-true-nature-their-cooperation

54 Ibid.

55 Fraser, Op. cit.

56 Ibid.

57 Maxim Trudolyubov, “China’s Balancing Act Between the U.S. and Russia”, Wilson Center, 24 May 2024, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/chinas-balancing-act-between-us-and-russia

58 Brahma Chellaney, “Growing China-Russia alignment signifies Biden policy failure”, Nikkie Asia, 31 May 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Growing-China-Russia-alignment-signifies-Biden-policy-failure

59 Fraser, Op. cit.

60 Chellaney, Op. cit.

61 Chellaney, Op. cit.

62 Fettweis, Op. cit. p 64.

63 Fettweis, Op. cit. p 63.

64 Ibid.

65 Chellaney, Op. cit.

66 Ibid.

67 Charlie Bradley, “Russia and China vs NATO: Military might compared as NATO dominates its enemies”, Express, 1 September 2022, https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1663402/russia-china-nato-military-compared-ukraine-taiwan-spt

68 Article 5 of the NATO treaty on collective defense provides that “if a NATO Ally is the victim of an armed attack, each and every other member of the Alliance will consider this act of violence as an armed attack against all members and will take the actions it deems necessary to assist the Ally attacked”, see “Collective defence and Article 5”, 04 July, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_110496.htm

69 “AUKUS: The Trilateral Security Partnership Between Australia, U.K. and U.S.”, U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Spotlights/AUKUS/

70 This term denotes China's strategic initiative to create a network in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

71 The Enhanced Defensive Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).

72 The Enhanced Defensive Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) Fact sheet, U.S. Embassy Manila, 20 March 2023, https://ph.usembassy.gov/enhanced-defense-cooperation-agreement-edca-fact-sheet/

73 Max Bergmann and others, “Collaboration for a Price: Russian Military-Technical Cooperation with China, Iran, and North Korea”, CSIS, 22 May 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/collaboration-price-russian-military-technical-cooperation-china-iran-and-north-korea

74 Janis Kluge, “Russia-China Economic Relations”, SWP, 16 December 2023, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/russisch-chinesische-wirtschaftsbeziehungen

75 Ibid.

76 Kelly Ng and Yi Ma, “How is China supporting Russia after it was sanctioned for Ukraine war?”, BBC, 17 May, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/60571253

77 “Brics: What is the group and which countries have joined?”, BBC, 1 February 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-66525474

78 Clara Fong and Lindsay Maizland, “China and Russia: Exploring Ties Between Two Authoritarian Powers”, Council on Foreign relations, 20 March, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-russia-relationship-xi-putin-taiwan-ukraine

79 Mackinder, Op. cit. p 437.

العودة إلى الجيوبوليتيك في ضوء الاصطفاف الروسي الصيني

العميد الركن ريمون فرحات

أضاف الاصطفاف الروسي الصيني تعقيدات جديدة على المسرح العالمي تستحق التوقف إزاءها لجهة مفاعيلها الجيوبوليتيكية المرتقبة في ضوء الأبعاد الجديدة التي أضيفت إلى مشهد الصراع الدولي القائم حاليًا، والتي تحاكي صورة الصراعات الدولية التي كانت قائمة في بداية القرن العشرين.

شكّلت النظرية التي أطلقها البريطاني هارفولد ماكندر (Harlford Mackinder) في مقال له في العام 1904 بعنوان «محور الارتكاز الجغرافي في تعاليم التاريخ» (The Geographical Pivot of History) فاتحة النظريات الجيوبوليتيكية الحديثة، والتي قدّم من خلالها مفهومه لقلب العالم ()HeartLand، معتبرًا قارات العالم القديم الثلاث قارة واحدة أطلق عليها اسم جزيرة العالم (World Island)، ومحددًا فيها منطقة ارتكاز (Pivot area) تضم شرق أوروبا، وليعود في العام 1919 ويسمّيها بمنطقة قلب الأرض ()HeartLand بعد توسيعها ناحية الغرب، وانتهى إلى اعتبار أن من يحكم شرق أوروبا يحكم قلب الأرض، ومن يحكم قلب الأرض يحكم الجزيرة العالمية، ومن يحكم الجزيرة العالمية يحكم العالم. كما شدد ماكندر على منع تركيز القوة في منطقة الارتكاز التي ستتوسع وتستفيد من مصادر هائلة تمكنها من بناء الأساطيل التي تؤهلها للسيطرة على الامبراطورية العالمية. وحذّر في هذا السياق إلى أن أي تحالف ما بين ألمانيا وروسيا يمكن أن يؤدي إلى ذلك. فهل يمكن للصين، في ضوء اصطفافها إلى جانب روسيا، أن تلعب دور ألمانيا الذي حذّر منه ماكندر؟

ففي ضوء الوضع القائم حاليًا، يصعب على الولايات المتحدة الأميركية بالتحديد، اعتماد منطق الدبلوماسية الثلاثية التي اعتمدتها في سبعينيات القرن الماضي لفك الارتباط بين الاتحاد السوفياتي والصين، خاصة في ضوء الترابط الاقتصادي العميق القائم حاليًا بين البلدين والتناغم السياسي بينهما على المسرح الدولي.

إن الترابط القائم ما بين قلب العالم بالمفهوم الماكندري والصين، يشكل قدرة تسيطر على مصادر قوة كبيرة، بالإضافة إلى الإرادة السياسية الفاعلة، التي توجب التعامل مع كل من روسيا والصين على أنهما مصدر تهديد واحد، فإهمال أحدهما أثناء التعامل مع الآخر لن يؤدي إلى نهايات ناجحة، وبالتالي إن محافظة الولايات المتحدة الأميركية على سيطرتها العالمية، يوجب عليها اعتماد استراتيجية كبرى (Grand Strategy) تأخذ في الاعتبار «التهديد» الصيني الروسي المشترك على ضوء مفاعيل الاصطفاف الحاصل حاليًا بين موسكو وبكين.