- En

- Fr

- عربي

The strategy of using external support in intrastate conflicts

Introduction

Empires had vanished, and so, too, had the Cold War. Brower argues that the early years of the twenty-first century bore little resemblance to the earlier decade. He states that Communism had disappeared from Europe and remade itself in China into a political dictatorship promoting capitalism. Also, the newly elected leaders of the former communist states slowly adopted a liberal democracy and restored free-market economies. He sees that the Western societies had moved in the half-century since the Second World War into a new Industrial Revolution and new global economy. Their living conditions were far different from those relics of outdated industrial life left behind by the communists[1].

Conflicts and wars create tremendous human costs for societies. They leave a negative impact on the social, political, and economic development of the states involved. Brower describes the twentieth century as a time of extreme violence and upheaval. Revolutions and wars destroyed the lives of millions of people throughout the world. Furthermore, Brower describes the closing years of the twentieth century as a period of ethnic conflicts so severe that they threatened the very survival of some new nation-states. He argues and deducts that the responsibility for these tragic events lay in large measure on ambitious leaders determined to seize and hold power regardless of the human consequences. He sees the world after the 2001 terrorist attacks and the 2003 Iraq war, as a very unstable and violent place[2].

On the opposite, these conflicts, and wars stimulated grandiose projects and high expectations for a better life for future generations. For Brower, destruction and creation are inseparable themes of history[3].

One of the main difficulties of conducting an effective insurgency against a government in intrastate conflicts is the asymmetry of the resources that the warring actors can efficiently assemble. To compensate for disparities in resources, non-state actors often undertake asymmetrical strategies such as irregular warfare. However, to achieve victory, non-state actors will need either to overpower the state or make the conflict extremely costly for the incumbent government. External support from third parties can help these non-state actors reduce the asymmetry between themselves and the state. Even though non-state actors might not get the high-end equipment and resources the government has, but medicine, food, ammunition, small to medium military arms, and eventually direct external military support might complement local resource mobilization and lead to a more fruitful insurgency[4].

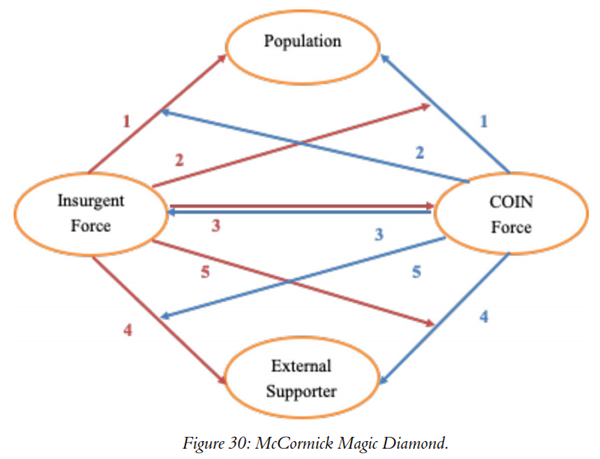

External support is the fruit of international relations and diplomacy between state actors or between state and non-state actors. International relations scholars have developed a variety of models to understand insurgency and to plan a good and effective counterinsurgency response. Dr. Gordon H. McCormick, Chair of the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) Defense Analysis Department (DA), established in 1994 a Model of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency to frame the information operations and the unconventional strategy used by the state. The ‘Magic Diamond’ model developed by McCormick has become the most respected model both in the academic and military context. In his model, McCormick develops a symmetrical assessment of the necessary actions for both the state forces and the insurgents to succeed. To this extent, the model can show how both the COIN forces and the insurgent fail or succeed. The model’s principles and strategies apply to both actors, thus the degree to which the actors follow the model would have a direct relationship to the failure or success of either the COIN force or the Insurgent.

In the McCormick's Model, the state and non-state actors use the similar five available strategies: strategy 1, gain the support of the local population; strategy 2, disturb the control of the adversary over the control of the local population; strategy 3, execute direct military actions against the adversary; strategy 4, gain external support from the international actors; and finally, the strategy 5 interrupt the external support sent by the international actors to the adversary. To succeed and win the conflict, these strategies should be executed in order; Strategy 1, 2 then 3, and simultaneously strategy 4 then 5.

In this article, based on the quantitative analysis, results found that some types of external support decrease the probability of winning, I will emphasize the weakness of this model regarding strategy 4 – external support from the international actors – and then draw a better and enhanced model that will increase the probability of winning for both actors. To reach the proposed enhanced model, I will proceed as follows. First, I will talk about the types of external support, then the data analysis results, after I will draw an S-shaped growth curve that represents the external support in time and the probability of winning. Once I describe the McCormick Magic Diamond, I will propose my enhanced model.

Types of external support

Since the end of the Cold War, during intrastate conflicts, external support has had a deep impact on the effectiveness of many non-state actors. State support had an important role in easing the political, logistical, and military actions of non-state actors. Even when external support did not take a crucial part in changing the outcome of the war, it has at least helped the non-state actors survive and gain prominence during conflicts. Even though states continue to be among the most active and important external supporters of non-state actors, Diaspora, refugees and other non-state actors also played a major role in providing support to non-state actors in their fight in intrastate conflicts. Nevertheless, in most cases, the range and scale of assistance that is given are significantly less than that of states[5]. In general, state supporters helped non-state actors sustain their armed conflicts and develop their overall political, financial and military capabilities. While these non-state actors were hardly able to defeat organized militaries on the battleground, in some cases, external state support at least aided them to deny the enemy of their states of easy and quick triumphs. In other examples, external support extended the conflict duration or increased the likelihood of a political agreement that was more advantageous to the non-state actors. Sometimes, external support has led non-state actors to victory[6].

In their book “State support for insurgencies”, RAND authors contend that, when determining the effect of external support, timing is critical. They also state that “Support is usually most valuable early in a campaign when it can prove central in establishing the insurgent group’s viability and thus enhancing its longevity”[7]. Since the logistic necessities are minimal or modest at best to create an insurgency, even poor states can easily ease its development. However, ensuring insurgency’s success is significantly more difficult to analyze and predict. Through the provision of training, arms, sanctuary, and cash, the supporting states have frequently taken an important part in increasing the resilience of emergent groups. External support is crucial for non-state actors especially when they face a powerful enemy. In our research, we will use the types of external support defined in the Uppsala Conflict Data Program Department of Peace and Conflict Research (UCDP).

With a history of almost 40 years and one of the first data collection projects for wars, UCDP is the world’s primary source of data collection on conflicts. UCDP produces “high-quality data, which are systematically collected, have global coverage, are comparable across cases and countries, and have long time series which are updated annually”[8]. Also, the program offers a distinctive supply of data and information for scholars and policymakers[9]. Continuously, UCDP updates and operates its database on organized violence and armed conflicts, in which information on many features of military armed war like conflict resolution and conflict dynamics is presented. In the UCDP definition, the external supporter is “a party providing external support. The external supporter needs not to be otherwise involved in any armed conflict; it can be a state government, a Diaspora, a non-state rebel group, an organization such as an NGO or IGO, a political party, a company, or a lobby group, or even an individual”[10].

Based on the types of materials and items offered by the external supporter, UCDP distinguishes between different kind of external support, “troops as a secondary warring party, access to military or intelligence infrastructure, access to territory, weapons, material/logistics, training/expertise, intelligence material, other forms of support, unknown support”[11]. In this paper I will use the same type of support defined in UCDP.

Before discussing our first model “the external support S-shaped model” – a model that represents external support in function of time and the probability of winning – in the next section we will summarize our data analysis findings regarding external support and the probability of winning.

Data analysis

At present, as during the entire period since World War II, Van Creveld sees that a handful of industrialized states detain approximately four-fifths of the world’s military power. These states spend in total four-fifths of all military funds. In 2017, the entire world military spending augmented to reach $1739 billion with a growth of 1.1% from 2016[12]. Also, in 2018, the overall military expenditures rose again 2.6% from 2017, to reach a total of $1820 billion. Of the 195 countries in the world, 15 countries spend $1470 billion representing 80% of all the military expenditures[13].

Van Creveld argues that, on one hand, and since 1945, the great majority of conflicts and wars have been low-intensity conflicts. On the other hand, he argues that in terms of both political results accomplished and casualties suffered, these conflicts have been incomparably more significant than any other[14]. Today, most conflicts and wars fall into the category of intrastate conflicts. From the period of 1946 until 2014, the UCDP recorded 259 conflicts[15]. Out of these 259 conflicts, 212 were intrastate wars between state actors (the government) and non-state actors (the rebel) representing 82% of all the conflicts, and 47 were interstate conflicts between state actors representing 18%[16].

In its 2016 yearbook publication, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) states that in the intrastate conflicts that occurred in the world since September 2001, and the military interventions of external states have more than doubled[17]. Additionally, SIPRI enunciates that, in recent years, the tendency has been for increased troop support or “boots on the ground”[18]. Depending on its practice, external support may be a crucial variable in conflict outcomes: it often prolongs the fighting, makes the conflict deadlier and leads to an increase of the threats and challenges associated with reaching a negotiated settlement. In intrastate conflict, supporting and aiding the participants turn out to be cheap, and an effective strategy to respond and reply to security concerns by distracting and weakening the rival engaging in these conflicts if not by squarely abolishing them.

The number of intrastate conflicts recorded by the UCDP that experienced some type of external intervention supports the SIPRI conclusion on interventions in intrastate conflicts. From the 212 intrastate conflicts recorded by UCDP, 144 conflicts have experienced some kind of external support from other states (70% of all the intrastate conflicts). These types of external support can vary from the direct participation of security and military personnel to indirect forms of support, such as access to intelligence infrastructure and material or material/logistics support, economic/funding, sanctuary or training/expertise. The study of external support in conflicts displays how types of support have changed over time and how types of external support actors receive, exemplify different kinds of conflict.

One will think that external supports increase the probability of winning for the receiver of this support, others think that external supports have a slight impact on the war outcome. To answer the question which factors and specifically which types of external support increase the probability of winning of actors in intrastate conflicts, we undertook multiple statistical tests to see which factors increase the outcome of wars. Using data from the UCDP data bank, Polity IV dataset and World Bank dataset, we applied several logistic regression models to analyze a set of independent variables that affect the outcomes in intrastate conflicts that occurred between 1991 and 2015. We applied three statistical analysis studies to find which independent variables influence the outcome of wars.

Based on the first statistical analysis results of the four independent variables, (per year of the conflict), the total number of fatalities in the conflicts that both parties endured, the number of states actors sending external support to the non-state actor, the duration of the conflict, the regime type (democracy or not) of the state conducting the conflict – and the two control variables (per year of the conflict) – the population number of the country where the conflict is conducted, and the GDP (gross domestic product) of the country, we found that, first, as the total number of deaths increases, the probability that state actors (governments) will win conflicts will decrease; second, as the number of external actors supporting non-state actors increases, the probability of the state winning will decrease; third, as the duration of the conflict grows longer, the likelihood of the state winning will decrease; fourth, as the number of casualties increases, the probability of the state winning will decrease; and, finally, even if the conflict duration increases, the probability of a democratic state winning in intrastate conflicts is higher than the probability of non-democratic state actors winning.

Based on the second statistical analysis results of the nine type of external support independent variables (per year of the conflict) – troops as a secondary warring party, access to military or intelligence infrastructure, access to territory, weapons, material/logistics, training/expertise, funding/Economic and intelligence material – we found that some types of external support sent to non-state actors increase their probability of winning against the state actors in intrastate conflicts, whereas, others decrease their probability.

Last, like the second statistical analysis, we found that some types of external support sent to states increase their probability of winning against the non-state actors in intrastate conflicts, whereas, others decrease their probability.

Summary, based on our quantitative study we confirm the subsequent hypotheses:

1- The increase in the total number of deaths in the conflict decreases the probability of winning of state actors.

2- The increase in the number of external supporters to the non-state actors decreases the probability of winning of state actors.

3- The longer the duration of the conflict also increases the probability of the non-state actors winning.

4- Democratic state actors have a higher probability of winning against non-state actors than do non-democratic actors in intrastate conflicts.

5- The increasing number of death in the conflict decreases the probability of the democratic state actors winning but it does not seem to affect the likelihood of non-democratic states winning.

6- When the number of death is relatively small, democratic states have a higher probability of winning than do non-democratic, but when the number of death will increase non-democratic states will have a higher probability of winning.

7- Sending Troops as secondary warring to the rebels, materiel/logistics support, funding/economic, intelligence material to help the non-state actors in their fight against the state will increase their probability of winning its war.

8- Allowing access to military or intelligence infrastructure/joint operations or access to territory or providing training/expertise to the non-state actors will decrease their probability of winning its war.

9- Training the State forces will increase its probability of winning its war.

10- Sending troops as a secondary warring party or providing weapons or intelligence material in the conflicts to help the State will decrease the probability of the state winning its war.

The external support S-shaped model

In this section, I will draw an S-shaped growth curve model that represents the external support in time and correlates it to the probability of winning. Before explaining this model, I will define the S-shaped growth curve.

The S-shaped growth curve (sigmoid growth curve) is a pattern of growth where initially the population density slowly increases in a positive acceleration rate – phase I; then the curve rapidly increases approaching an exponential growth rate – phase II; then the curve declines in a negative acceleration phase until it reaches a zero growth rate and the growth stabilizes – phase III[19]. The positive acceleration phase happens because of the new environment. At the end of the curve, the slowing of the rate of growth reflects, in this case, the fullness of the organism. The ‘carrying capacity’ or the ‘saturation value’ (symbolized by K) is the zero growth rate or the point of stabilization of the environment. The value K denotes the threshold where the upward curve begins to flatten and the growth to stabilize. This model is produced when altering population numbers plotted over time[20]. In my model, I will add another threshold that I will call the ‘critical value’ symbolized by J. I will discuss this critical value in the next paragraph.

Receiving external support in intrastate conflicts is crucial for non-state actors winning. Alternatively, preventing these non-state actors from receiving external support is also crucial for state victory. Some scholars see external support as an important factor in making the actors winning their wars. Others link conflict duration to external support by stating that, when non-state actors receive external support, it increases the conflict duration. And few don’t see a link between external support and winning. Given all that, and from the statistically significant results, I can argue that: some types of supports increase the probability of winning; however, to succeed in intrastate conflicts, time is crucial for both actors; and trying to stop the external support from reaching the ‘critical value’, J, is also the most important issue.

External support usually follows the pattern of the S-shaped growth curve. At the beginning of the conflict, external support afflux at a slow pace. This is due to many reasons, from lack of cooperation, to lack of favorable ground, and to the control of the ground by the state. In this phase, non-state actors are searching for potential external supporters via their international relations. All these reasons make the external support reach the non-state actors at a low pace.

After the slow increasing pace, the external support will follow an increased and rapidly exponential form. This happens mainly because, in this phase, the ground is now suitable for external support to reach the non-state groups. Non-state actors now have a certain control on the ground that makes external support reach them freely and easily. The international relations that non-state actors have built-in phase I, now have flourished and external support from states or non-state actors begins to arrive.

In phase III, we see a decline in a negative acceleration until the external support reaches a zero growth rate until it stabilizes. This decline in the growth rate represents the increasing environmental resistance that becomes proportionately more important at higher population densities. Environmental resistance is “The total sum of the environmental limiting factors, both biotic and abiotic, which together act to prevent the biotic potential of an organism from being realized”[21]. In our research, such factors include the availability of external support for the non-state actors (e.g. food, money, weapon…). Now, non-state actors have reached the saturation capacity in external supports, and they cannot handle more incoming supports due to their relatively small organization and they do not need more because of their superiority on the ground.

For the state to win, it should prevent the external support to the non-state actors to reach the J threshold level. If the state achieves to do that, the likelihood of the non-state actors to win will be minimal. On the contrary, if the external support reaches the K threshold level, the likelihood of the non-state actors to win will be maximal. Otherwise, the external support will increase the conflict duration, and will not give the non-state actors the superiority to win the conflict.

Business Dictionary defines equilibrium as a “State of stable conditions in which all significant factors remain more or less constant over a period, and there is little or no inherent tendency for change. For example, a market is said to be in equilibrium if the amount of goods that buyers wish to buy at the current price is matched by the amount the sellers want to sell at that price. Also called steady state”.

In this paper, we will refer to external support equilibrium to be in equilibrium when the amount of external support that non-state actors need is matched by the amount it receives. In phase I, the model will not be in equilibrium because the amount of external support needed by the non-state actors will be less than the amount of support received. In phase II, the model will also not be in equilibrium because the amount of external support needed by the non-state actors is more than the amount of support received. Only in phase III, the model will be in equilibrium because the amount of external support needed by the non-state actors will be equal to the amount of support received.

All this will let us draw our model regarding external support in time and the probability of winning of non-state actors in intrastate conflicts.

Pattern 1: if the external support reaches the ‘saturation value’ threshold, the probability of winning of the actors receiving the external support will be high and they will have the superiority of winning. After this threshold, the actors receiving the support will have sufficient support that they can have superiority in the conflict.

Pattern 2: if after a certain time the external support surpasses the ‘critical value’ but does not reach the ‘saturation value’, the external support will extend the conflict duration and the conflict will grow longer.

Pattern 3: if the external support does not reach the ‘critical value’, the probability of winning for the actors receiving these supports will be minimal. Below this threshold, the actors receiving the support will not have sufficient support that will give them superiority in the conflict.

McCormick Magic Diamond Model

Dr. Gordon H. McCormick, advanced in 1994 his ‘Magic Diamond’ model to frame the information operations and the unconventional strategy to be used by the state. McCormick’s Model of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency also referred to as the ‘Magic Diamond’, is an analytical model that analyzes the conflicts between the government and non-state actors. In his model, McCormick takes into account four actors: the state, the counter state or insurgency, the population and the international actors[22].

McCormick defines the first element in his model as ‘the state’. The state is the incumbent government that is required to fight the insurgent. The second actor is ‘the counter state’ or ‘insurgency’. This actor mainly involves the insurgent rebel that contests the status quo of the state. These non-state actors also may involve individuals, groups or organizations that actively or even passively fight alongside the rebel force to repel the military operations of the state. One of the key goals of the non-state actors is to defeat the incumbent regime to establish a new government. The third actor that McCormick defines is ‘the population’. This actor consists of all the non-combatant individuals that live in the state and who have the means to support either side (the state actor or the non-state actor). The fourth actor defined by McCormick is ‘the international actors’. According to McCormick, these actors are the international organizations, external states, or Non-Governmental actors (non-state supporter actors) that are directly or indirectly involved in the conflict by taking sides and sending support to either the state or non-state actors.

In the era of transnational and global economic welfares where the state and the rebel generally obtain external support from the international actors, the McCormick model visualizes intrastate conflict as a correlation between two interdependent dynamic systems – one characterized by the state actor and the other by the non-state actor or insurgents. This interactive action between these actors is a zero-sum game to control both the political space and the local population. In this model, both state and non-state actors try to gain the control and the support of the local population while denying the opponent the same advantage. The struggle among these actors is a dynamic process that occurs within the existing geopolitical, cultural, social and economic contexts. Nonetheless, the predominant settings that rule this asymmetric war between the state non-state actors are: the state always starts the conflicts with a major force advantage over the insurgents; instead, the insurgents have an information advantage over most state actors.

The information advantage of the insurgents lies in their ability to continuously gather information on the government and use it as propaganda. Because most of the governmental buildings and infrastructures are well known, the insurgents can easily see the government. On the contrary, because usually the insurgent will be hidden, it is almost impossible for the government to see them. By exploiting its information warfare capabilities, the insurgents can easily level the force’s disadvantage. Thus, the main challenge of the government, if it wants to increase its winning probability, is to transform its force advantage into an information advantage. However, the rebels are in a much superior situation to control the assisted preferences of the local population because the insurgents are entrenched amid the population and know them better than the state. Rather than the objective degree of communication with the local population that most state actors seek to have, embedding permits the rebels to create better communication with them.

Operational strategies for warring actors

In McCormick's model, the correlation between the state and non-state actors is such, individual actions can have multiple effects on each other. Therefore, numerous strategies and tactics may be derived from the McCormick Model. As briefly described in the introduction, the different operational strategies on McCormick's model of insurgency are represented in the figure below by arrows and numbers. In the model, the same five strategies are available for both actors: strategy 1, gain the support of the local populace; strategy 2, disrupt the control of the opponent over the local population; strategy 3, take direct action against the adversary; strategy 4, work on gaining the support of the external supporter; strategy 5, disrupt the support of the external supporter for the opponent. To succeed these strategies should be executed in order; Strategy 1, 2 then 3, and simultaneously strategy 4 then 5.

Strategy 1: Gain the support of the local population

Gaining the support of the local populace is a primary element in intrastate conflicts against the opponent. The support of the population assists the state actor to obtain information and insight about the rebel and its actions. The local population inadvertently supports the insurgency when it does not provide the regime with information about the rebel. The absence of adequate and proper information about the rebels touches directly the ability of the state to quickly reply to their menace. Nevertheless, when the population collaborates with the state, by providing vital information about the rebels, for example, the state will be better prepared to fight these non-state actors. Therefore, to effectively counter an insurgency, it is in the state’s greatest interest to gain the support of the local population. Dr. McCormick states, “no matter how weak the state is, with appropriate information it can destroy the insurgency”[23].

Also for the rebels, the local population characterizes a valuable benefit. In addition to providing valuable information about the states and their activities, the population supplies the rebels with economic resources and weapons. Most considerably, by allowing the rebels to mix with the local population and the possibility to hide from the counteractions of the incumbent government, the population’s support offers to these non-state actors a vigorous environment. The correlation between the population and the rebel is so special that McCormick sees that “any part of the population not controlled by the government is likely to be controlled by insurgents”[24]. While the state looks to gain popular support, the insurgency, on the contrary, expects to gain force multipliers. Based on the feedback acquired from the communication with the population, the actions of the warring actors towards the local populace are subject to continuous alterations. Eventually for the warring actors, gaining the support of the local populace is the foremost decisive and significant element to win in intrastate conflicts.

To gain the support of the population, many tools can be used. From propaganda and the use of mass media to bribe the locals are an example of the important tool actors can use to achieving this step.

Strategy 2: Disrupt the control of the opponent over the population

Because the population’s support is vital in defeating the opponent, oppressing the link of the adversary with the local population is a primary goal throughout the conflict for the state and the non-state actors. To accomplish this and delegitimize the adversary’s authority, both the warring actors continuously attempt to break the adversary’s relationship with the local populace. Consequently, it is crucial for both actors to gain and preserve a certain level of legitimacy and be able to win the sympathy of the populace.

Strategy 3: Direct action

Ultimately, after that the two adversaries have gained strength, gathered information about each other, and gain support from the local population, they are now capable of launching direct attacks against each other. These direct attacks aim to disturb the opponent’s military actions, capture or destroy troops, and weaken the motivation of the enemy to continue fighting, in sum to win. Still, the support of the local population remains the key factor for both actors to win.

Strategy 4: Compete for the favor of external supporters

In this context, the conflict to gain the support of external actors is also vital for the state and the non-state actors. As a result, both adversaries are continuously attempting to legitimize their situations to maintain and gain support from external actors. Based upon the reaction and feedback acquired from the interaction with the external actors, the tactic of competing for support from the international community is also subject to regular alteration.

Strategy 5: Disrupt the support from external supporters to the opponent

When external actors are involved amid the state and the rebels in intrastate conflicts, it is crucial for both parties to delegitimize their opponents in the eyes of the international community to deprive them of external support. External support is crucial for the state and the rebels in this zero-sum game: it affects directly the outcome of wars. Again, the tactic of disrupting support from the international community continuously depends on the continuous feedback acquired from the interaction with external actors.

A Model for winning wars: the Pentagon Diamond

The McCormick Magic Diamond has a main weakness: The weakness that appears in the model resides in the fact that McCormick did not take into consideration that some type of support may affect differently the outcome of wars. There are two types of support: supports that have a negative impact by lowering the probability of winning, and support that have a positive impact on the outcome of the war by increasing the probability of winning. Based on the number of conflicts that happened since 1991, and the statistical analysis results of these data, two types of support appear to affect differently the outcome of wars. On one hand, some types of external support to the actors affect positively the outcome of war meaning that it increases the probability of winning. On the other hand, some other types of external support affect negatively the outcome of war meaning that it decreases the probability of winning.

Based on this finding, strategy 5 has to be updated, and a new strategy has to be added. In strategy 5 – disrupt the support from external supporters to the opponent – McCormick concludes that when external actors are involved in intrastate conflicts between the government and the rebels, it is crucial for the warring parties to “delegitimize their respective enemy in the eyes of the international community to deprive it of its support”[25]. He adds by saying, “External support is a very significant factor for the state and the insurgency in this zero-sum game: it affects directly the outcome of wars”[26].

Nevertheless, based on the statistical finding, I can argue that: regarding his saying that it is crucial for the warring parties to “delegitimize their respective enemy in the eyes of the international community to deprive it of its support”[27], McCormick did not take into account that for some type of external support, it would be better not to delegitimize but to emphasize and to encourage some types of the support received by their respective opponent in the eyes of the international community and the local population because they have a negative impact on the war. Also, in the second statement of McCormick that external support is a very important factor for the state and the rebels in this zero-sum game and it affects directly the outcome of wars, our statistical analysis showed that some external support affects positively the outcome of wars and other affect it negatively.

This will make us update the McCormick model by splitting strategy 5 into two strategies: strategy 5 and 6. In strategy 5, we have to define what we have to delegitimize in the eyes of the international community and the local population only the type of support that has a positive impact on the war outcome and increases the probability of winning of the actors. On the opposite, in the new strategy 6, we have to define that we have to ‘emphasis’, ‘encourage’ and ‘qualify’ in the eyes of the international community and the local population the type of support that have a negative impact on the war outcome and decreases the probability of winning of the actors.

Conclusion

To understand the future, study the past. The State is somewhat a recent creation, and its rise indeed to governance is a unique purpose for calling ours the ‘modern’ age. Van Creveld asked an inquiry as to what upcoming civilizations will go to war for is virtually immaterial. He concludes that it is just not right that war is not entirely a ‘means to an end’, nor that societies essentially fight to reach this or that objective. Actually, he claims that the opposite is true. Van Creveld concludes that societies frequently adopt one objective or another to fight. Although the usefulness of war as a way for achieving practical ends can be questioned, its capability to fascinate, inspire and entertain has never been in doubt[28]. Van Creveld also concludes that an important way in which people can attain happiness, joy, freedom and even ecstasy, is by not remaining home with their wife and family, even to the point where, often enough, they are only too pleased to give up their dearest and nearest in service of war[29].

Kenneth Waltz sees that Humans will continue to fight wars; he said, “If one asks whether we can now have peace where in the past there has been war, the answers are most often pessimistic”[30]. Therefore, to win wars, it is essential to discover and better understand what affects the outcomes of wars. In this paper, I have studied the effect of external support on conflict outcome and drew two models for external support.

Because we are in the era of modern warfare, and because the defense communities are challenged with asymmetric warfare, the wider implications may be studied in future research. Understanding the mechanics of asymmetric warfare is essential for success in a war where external support plays a crucial role. In principle, from such theoretical knowledge of asymmetric warfare, both sides can benefit the relatively stronger and relatively weaker one.

In this paper, we drew two models that can affect the outcome of the war in intrastate conflicts. The first model is an S-shaped growth curve model that represents the external support in time and the probability of winning. This model characterizes how external support increases the likelihood of winning wars when it reaches the saturation level and how it decreases when it does not reach the critical level. Secondly, we emphasized the weakness of the McCormick model regarding strategy 5 – external support from the international actors – and then drew a better and enhanced model that will increase the probability of winning for both actors.

In the enhanced model, we updated strategy 5 by stating that what we have to delegitimize in the eyes of the international community and the local population only the type of support that has a positive impact on the conflict outcome and increases the probability of winning of the actors. Furthermore, we added a new strategy, strategy 6, stating that we have to ‘emphasis’, ‘encourage’ and ‘qualify’ in the eyes of the international community and the local population the type of support that has a negative impact on the conflict outcome and decreases the probability of winning of the actors.

The McCormick Magic Diamond has a main weakness: the one that appears resides in that the type of support may affect the outcome of wars differently. There are two types of support: types of support that increase the probability of winning and types of support that decrease it. Based on the data and the statistical analysis these types may affect positively or negatively the outcome of the wars. In this article, we addressed the gap in the arena of conflict outcomes by studying ways to increase the probability of winning in intrastate conflicts by choosing proper types of external supports. To reach a finding, we used a statistical analysis approach on the intrastate conflicts that occurred since 1991.

To study the strategy of external support, we started by enlightening how and why external actors get involved in conflicts. By including timing into the analytical structure, we provided more suggestions about decisions on when to send support and what the opponent should do to win the war. I found that to win in intrastate conflicts, the adversary should stop the afflux of external support before it reaches a certain threshold.

When thestrategic interests of their “protégé” are at risk, external supporters tend to rapidly undertake biased and unilateral interventions. So, when intrastate conflicts threatened their critical interests, supporters will likely use violent methods.

However, common interests of the supporting states may on the opposite ease a concession between them for multilateral intervention to reach a peace deal. Furthermore, the statistical results showed that certain types of support are likely to be more beneficial to the actors than others, but even if they are not properly used they tend to backfire on the beneficiary. Motivated by shared interest with their “protégé”, external supporters try to affect the outcome and duration of intrastate conflicts. To do so, external supporters attempt to favorably alter the balance of power to generate a quick success for their ally by sending them more support. Therefore, external support will likely reduce the force disadvantage gap between the rebel and the government on one hand, and external support may reduce the information disadvantage gap between the government and the rebel on the other hand.

Why do external supporters fail to accomplish their best outcome? While external supporters consider the efficiency of sending support to their supporters who do not have enough resources to win on their own, on the contrary, this may provoke a backlash from the opponent and the local population, thus involuntarily serving the opposing actor to increase its power. Therefore, I updated the McCormick Model so it captures the selective support that may initiate a backfire effect. The simulation results of the statistical study of intrastate conflicts made me conclude that while some type of support enables one actor to win, others may backfire and makes it difficult for the actor to be a dominant control, thereby leading to a defeat or military stalemate and thus prolonging the conflict.

Bibliography

- Byman, Daniel, Peter Chalk, Bruce Hoffman, William Rosenau, and David Brannan. Trends in Outside Support for Insurgent Movements. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2001.

- Environmental resistance, A Dictionary of Ecology, Encyclopedia.com. (June 5, 2019). https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/environmental-resistance.

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/earth-and-environment/ecology-and-environmentalism/environmental-studies/s-shaped-growth-curve.

- https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2018/global-military-spending-remains-high-17-trillion.

- https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2016/04.

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/.

- McCormick, Gordon. Seminar in Guerrilla Warfare class notes. Naval Postgraduate School, summer 2017.

- Number of Conflicts, 1975–2016, Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, http://ucdp.uu.se/.

- Van Creveld, Martin. Transformation of War. Riverside: Free Press, 1991.

- Waltz, Kenneth. Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959.

[1]- Brower, the World in the Twentieth Century: From Empires to Nations, 446.

[2]- Brower, The World in the Twentieth Century: From Empires to Nations, 447.

[3]- Daniel R Brower, The World in the Twentieth Century: From Empires to Nations. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), 1.

[4]- Adam Parente, 2015, The Impact of External Support on Intrastate Conflict. Clocks and Clouds 5 (1), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1583

[5]- Byman, Chalk, Hoffman, Rosenau, and Brannan, Trends in Outside Support for Insurgent Movements, 9-40.

[6]- Ibid.

[7]- Ibid.

[8]- Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Department of Peace and Conflict Research.

[9]- Ibid.

[10]- Ibid.

[11]- Ibid.

[12]- https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2018/global-military-spending-remains-high-17-trillion.

[13]- https://www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/.

[14]- Martin Van Creveld, Transformation of War (Riverside: Free Press, 1991), 25.

[15]- “Number of Conflicts, 1975–2016,” Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, http://ucdp.uu.se/.

[16]- Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Department of Peace and Conflict Research.

[17]- https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2016/04.

[18]- Ibid.

[19]- https://www.encyclopedia.com/earth-and-environment/ecology-and-environmentalism/environmental-studies/s-shaped-growth-curve

[20]- Ibid.

[21]- Environmental resistance, A Dictionary of Ecology, Encyclopedia.com. (June 5, 2019). https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/environmental-resistance.

[22]- Gordon McCormick, Seminar in Guerrilla Warfare class notes (Naval Postgraduate School, summer 2017).

[23]- McCormick, Seminar in Guerrilla Warfare class notes.

[24]- Ibid

[25]- Ibid.

[26]- Ibid.

[27]- Ibid.

[28]- Van Creveld, Transformation of War, 226.

[29]- Ibid.

[30]- Kenneth Waltz, Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis (New York: Columbia University

Press, 1959), 1.

استراتيجية استخدام الدعم الخارجي في النزاعات المسلحة داخل الدول

في ضوء استمرار النزاعات المسلحة داخل الدول وفي سياق التدخل الأجنبي واسع النطاق، وفي محاولة لحل التناقضات بين النظريات المتناقضة بشأن العوامل التي قد تؤثر على نتائج الحرب والنماذج التي تزيد من احتمالية تحقيق النجاح داخل الدول المتصارعة، نعرض في هذه المقالة أولًا التفاعل بين أربعة متغيرات: عدد الوفيات وحجم الدعم الخارجي ومدة الصراع ونوع نظام الدولة، واحتمال فوز الدولة على المنظمات المسلحة غير الحكومية.

إضافة الى ذلك، نعرض التفاعل بين كل نوع من أنواع الدعم الخارجي – القوات المسلحة كطرف متحارب ثانوي، والوصول إلى البنية التحتية العسكرية أو الاستخباراتية، والوصول إلى الأراضي والأسلحة والمواد/اللوجستيات والتدريب/الخبرة والتمويل/المواد الاقتصادية والاستخباراتية – المرسلة إلى الأفرقاء المتحاربة واحتمال الفوز. باستخدام التحليل الإحصائي ونماذج الانحدار اللوجستي(logistic regression) للصراعات داخل الدول التي حدثت بين العامَين 1991 و2015، نستكشف آثار الدعم الخارجي على نتائج الصراعات.

تم تنفيذ مواصفات المتغيرات المستقلة من خلال تحليل ومقارنة سلسلة من مجموعة بياناتUppsala Conflict Data وPolity IV ومجموعة بيانات البنك الدولي. استنادًا إلى نموذج McCormick Magic Diamond. اقترحنا في هذه المقالة تصوّرًا جديدًا لدراسة العوامل التي تؤثر على نتائج الحروب في النزاعات داخل الدول وقدّمنا نموذجَين جديدَين يزيدان من احتمالية الفوز في النزاعات الداخلية.